It is sometimes surprising that the name Sweyn Forkbeard is not more famous, as he was the first Viking to successfully make himself King of England, not to mention Denmark and Norway.

He only held the title for five weeks, but if it wasn’t for his untimely death, the history of England could look very different.

Viking Nobility: Father vs Son

Sweyn Forkbeard was the son of Harald Bluetooth, one of the first kings of a united Denmark.

Bluetooth converted to Christianity to facilitate a peace agreement with the Holy Roman Emperor in around 960.

The young Sweyn was probably baptized at this time.

In the mid-980s, Sweyn reportedly revolted against his father and took control of Denmark, with some critical Christian sources describing him as a staunch pagan at the time who would only convert later in life.

This is unlikely, he was probably raised Christian.

One of those critical sources, Adam of Bremen, also claims that there was pushback against Sweyn as a usurper and that he was exiled from Denmark for a period during which he lived in Scotland.

But overall, the evidence is that Sweyn successfully took his father’s position and became the accepted King of Denmark.

One of Sweyn’s first acts was to expel the bishops from Germany that his father had installed in Scania and Zealand.

But that this was an act of paganism is inconsistent with the evidence that Sweyn built churches in Denmark, notably at Lund and Roskilde.

It was more likely that he objected to political interference by the German church and the Holy Roman Emperor in what he considered Danish affairs.

This is supported by the fact that Sweyn later imported priests and bishops from England rather than Germany.

Viking vs Viking: Conquest of Norway

Viking rulers often vied for influence in neighboring Viking territories, and Sweyn’s father Harald Bluetooth had already established a foothold in Norway before he was ousted by Sweyn.

This gave Forkbeard an opening, and he built an alliance with Olof Skotkonung, the king of Sweden, and Eirik Hakonarson, the Jarl of Lade in Norway.

Together they took on King Olaf Tryggvason of Norway.

Surviving sagas about the events suggest that it was because of Olaf Tryggvason’s rejected marriage proposal to Sigrid the Haughty of Sweden and subsequent problematic marriage to Thyri, a sister of Sweyn.

It is suggested that the women pushed Sweyn to action in response to the insult.

But it may also just have been an opportune moment.

Olaf had made himself unpopular in Norway with the harsh tactics he used to ensure conversion to Christianity and loyalty to the crown.

Whatever the immediate motivation, the coalition attacked Olaf in the Baltic Sea when he was sailing home in what would become known as the Battle of Svolder in 999 or 1000.

Olaf suffered a decisive defeat, though legend says that he may have survived and continued to show up throughout history as one of those phantom historical figures who never died.

He was even reported as being in the Holy Land.

The victors divided control of Norway between them, with Sweyn taking the Viken district in the south, facing Denmark across the sea.

Revenge in England

Around the turn of the millennium, Sweyn turned his attention to England.

Some sources suggest that this was specifically in response to the St Brice’s Day Massacre.

This happened on 13 November 1002 when Aethelred the Unready, then king of England, ordered the slaughter of many Danes living across England in response to increased raiding activity over the previous years.

There is archaeological and textual evidence to suggest that Danish men living in England were killed en masse.

Mass graves potentially linked to the massacre have been found at Oxford and Ridgeway Hill.

Sweyn may have felt the need to retaliate as king of the Danes, and it may have been raids carried out by his men that prompted the massacre.

One source also suggests that his sister Gunnhilde and her husband Pallig Tokesen were both killed in the massacre, making it personal.

But it may also just have been an opportunity to enrich himself in England.

Before setting off, he arranged the right to sell spoils to the Duke of Normandy.

Sweyn and his men raided Wessex and East Anglia in 1003-1004 before famine forced them to return to Denmark in 1005.

But they returned in 1006-1007 and 1009-1012, though it is unclear whether Sweyn himself was present, or if the raids were carried out on his behalf by Thorkell the Tall, the leader of the Jomsvikings.

In either case, it enabled Sweyn to extort large amounts of Danegeld from the population.

But despite taking money not to raid, Forkbeard launched a full-scale invasion of England in 1013, probably seeing the weakness of his enemy and the opportunity to enhance his territory.

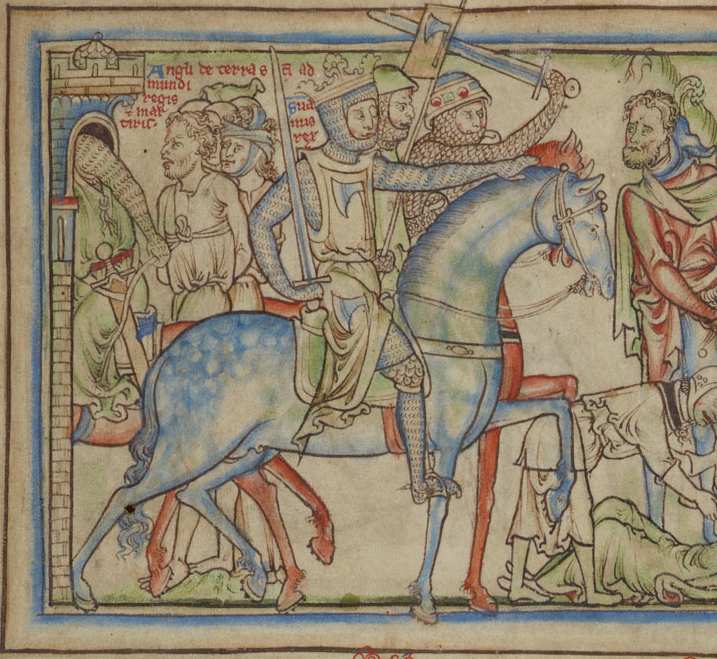

According to the Peterborough Chronicle, which is part of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Sweyn landed his fleet at Sandwich, which is near Dover in the south of England, and sailed up the Humber River to attack East Anglia.

While we don’t know the size of his force, it seems to have been overwhelming.

First, the earl of Northumbria submitted, then the Kingdom of Lindsey, and then the Five Boroughs, which were the five major Danish towns in Mercia.

He took hostages from every kingdom that submitted and required them to provision his men.

This meant that his men were fresh when they went south to Oxford, where it is known that St Brice’s Day Massacres happened, followed by Winchester, London, and Bath.

Aethelred was forced to send his two sons Alfred and Edward to Normandy for protection, to the same Duke of Normandy who had agreed to buy English spoils of war.

He followed them into exile by the end of the year 1013.

This allowed Sweyn to set himself up as the new king of England in Gainsborough in Lincolnshire.

But he was not able to enjoy his gains because he died in unknown circumstances on 3 February 1014.

His body was returned to Denmark to be buried.

Fighting Over Leftovers

If it wasn’t for Sweyn Forkbeard’s untimely demise, it is difficult to know what England would look like today.

Everyone could be speaking Danish instead of English.

But after his death, Sweyn’s eldest son Harald II succeeded him in Denmark and his younger son Cnut, who had accompanied him on the campaign, succeeded him in England.

While he battled with Aethelred and his son Edmund for control initially, by 1016, England was under Cnut’s command.

He also took control of Denmark following his brother’s death in 1018/9, and later took control of Norway, parts of Sweden, Pomerania, and Schleswig, forming the North Sea Empire.

When Cnut died in 1035, he was succeeded by his son Harold Harefoot, and two years later by his other son Harthacnut.

When he died in 1042, Harthacnut was the last Dane to rule in England, but this end was more a fizzle than a bang.

Harthacnut was the son of Cnut with Emma of Normandy, who had previously been the wife of Aethelred the Unready.

When he died, leaving his mother in England, she called her son Edward, Harthacnut’s half-brother and the son of his father’s old enemy Aethelred, to rule in England.

So, rather than regain their territory, the Wessex line got it back by default due to a lack of other suitable heirs.

So, it seems that what the Danes needed to take control of England at the start of the 11th century wasn’t more swords, but a few more male heirs.

If that were the case, we might find ourselves talking about Sweyn Forkbeard the same way we talk about William the Conqueror (again of troublesome Normandy).