We have previously talked about the pagan Norse Yule traditions that have found their way into modern Christmas celebrations, and the clear parallels between the figure of Father Christmas and the god Odin.

But today, let’s look at some of the traditional Celtic traditions still lingering in modern Christmas celebrations.

Winter Solstice

Of course, like the Norse, the Celts did not celebrate Christmas, taken from “Christ’s Mass,” since the pagans did not believe in Jesus.

Instead, they celebrated the Winter Solstice, called Grainstad or Gheimhridh by the Irish Celts. It fell on the shortest day of the year, between December 20 and 23rd.

It is worth noting that December 25th wasn’t chosen for Christmas because of its proximity to the solstice.

It was arbitrarily chosen, following the tradition of the Roman emperor choosing a day for their birthday celebrations.

Rather, it was because it was exactly nine months after March 25, Annunciation, the day it was believed that the Archangel Gabriel appeared to Mary and told her that she would carry the son of God.

The actual date of the birth of Jesus is not recorded in the Bible.

For most ancient societies that lived by the seasons, the solstices were important days of the year.

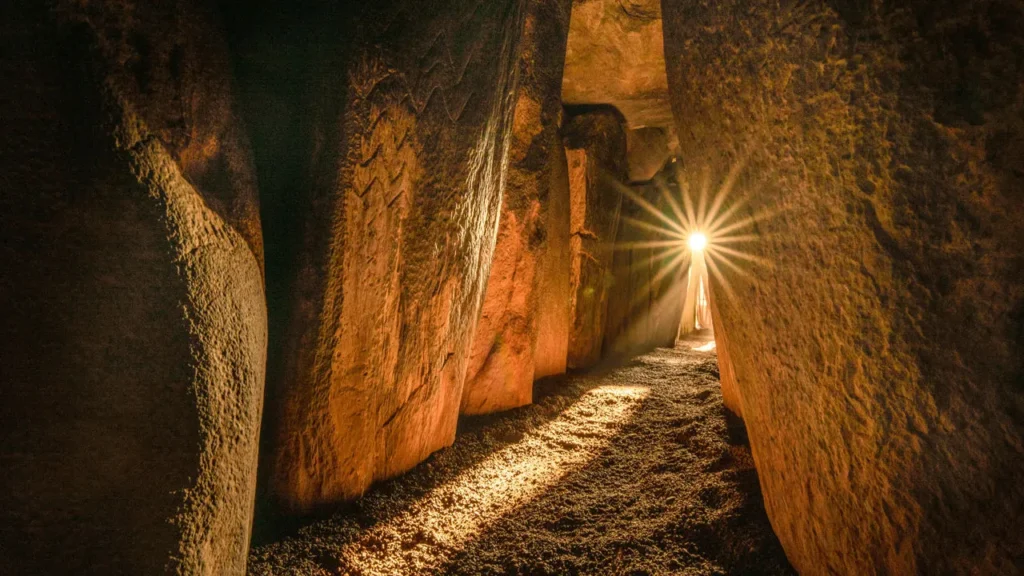

But we know that the Celts placed particular significance on the solstices since some of their Neolithic monuments, for example at Newgrange in Eire, Ireland, Maise Howe in Orkney, Scotland, and Bryn Celli Ddu in Wales were aligned to capture the rays of the sun during the solstices.

Newgrange is a stone passage tomb, related to sites such as Stonehenge but buried under a mound.

These were believed to act as passages between the world of the living and the spirit world.

On the day of the Winter Solstice, as dawn breaks, a narrow beam of sunlight enters the burial chamber, illuminating it in a spectacle of light.

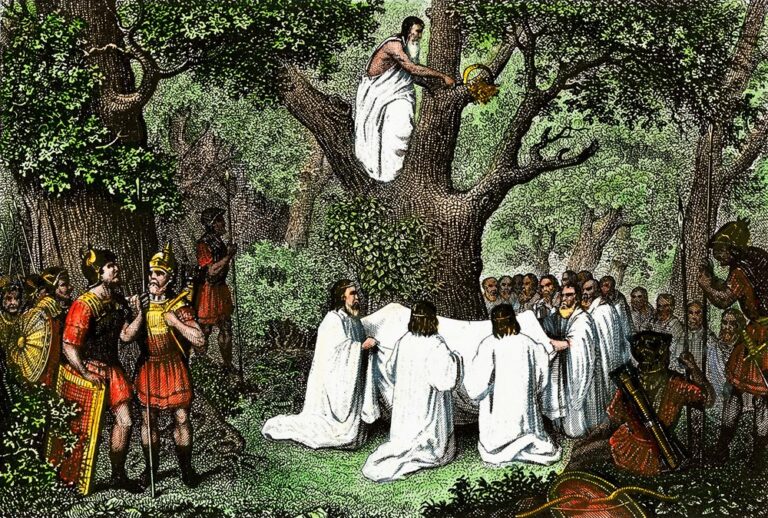

According to the Roman author Pliny the Elder, observing Druids among the Celts in Germania in the first century CE, the Druids gathered on the Winter Solstice and, among other things, gathered mistletoe from oak trees.

Mistletoe was believed to have magical and health-giving properties and could only be harvested by Druids during the solstice due to its sacred nature.

They caught the mistletoe in special cloths because it was believed that it should not touch the ground.

The Sun God Lugh

The ancient Celts believed that during winter, the sun god Lugh went “south,” which meant he traveled to the “otherworld” of gods and spirits.

Because he left, he took the warmth of the sun with him.

The Celts wanted to ensure that Lugh would find his way back, so they built bonfires to attract him back to their light and warmth.

Due to the extended hours of darkness and the dangers of winter, including cold, famine, and snowstorms, it was considered a dangerous time of year.

The Celts also believed that this was the time of year when the veil between the worlds was at its thinnest and spirits could visit from the Otherworld and cause mischief.

Another part of the protection rituals for the winter and to ensure the return of Lugh was to offer him animal sacrifices.

This was accompanied by celebrations during which the community shared the slaughtered meat.

It was believed that when animals were sacrificed part of the meat was reserved for the gods and the other part for men.

Strangely enough, men got the best bits!

To decorate for these celebrations, they often placed shiny objects on evergreen trees, including stars, a practice still evident in the modern tradition of Christmas trees.

Respiratory infections were also more common during the winter due to the effects of cold on the immune system.

Before the advent of modern medicine, catching a severe cold or flu could be a death sentence.

Noticing that some plants and trees remained alive during the winter while others died led to a belief that these plants contained powerful magic.

This was the source of the tradition of bringing evergreen trees into the home, as well as plants such as ivy, holly, and mistletoe.

Holly trees were considered sacred and could not be cut down, but sprigs of holly were thought to protect against evil.

Mistletoe was also believed to protect against evil, and used to create medicines, though we know today that most types of mistletoe are poisonous.

Cailleach, Goddess of Winter

While Lugh was away in the Otherworld, the power of Cailleach, the goddess of winter, grew.

She reigned from Samhain (November 1) until Beltane (May 1).

She was believed to be a shapeshifter, and while she most often appears as an elderly woman in a veil, this belied her true powerful nature.

She was believed to be a creator goddess who created much of the landscape and was also responsible for harsh weather, such as winter and storms.

She was also a mother goddess, being the mother of most of the gods and also the ancient first generation of men.

Some Celtic people believed that on February 1st, Cailleach would find that her supply of wood was running low, so she would go out to collect more, often causing particularly bad weather on that day.

But this was a sign that Cailleach would be relinquishing her power soon and that the winter would be short.

If the weather was good on February 1st, it meant that Cailleach had not yet come out to collect more wood, and therefore it would be a long winter.

Modern Pagan Traditions

Modern pagan traditions for the Winter Solstice draw on Celtic roots among other things to create new rituals that connect with nature and the wheel of the year.

For neopagans, the Winter Solstice is often treated as a night of personal reflection, used for meditation and self-insight from sunset until sunrise.

It is the ideal time to do this kind of personal work as it is the start of a period of growth as each day gets longer.

Lighting a bonfire or a candle is also part of a ritual to banish dark energy and invite light and positivity back into the person.

While engaging with the flame, pagans reflect on the lessons of the previous year and engage in the practice of forgiveness, of themselves and others, to banish the darkness of anger and resentment.