Did you know that the Vikings were contemporary with the Crusades that saw Christians from the West try to recapture Jerusalem ?

The Vikings were already officially converted to Christianity when the Crusades began, though pagan traditions continued. However, the Vikings did not join the main Crusades into the Holy Land.

Instead, they had conquests in northern Europe authorized by the Church in the name of converting pagans, though the now-Christian Vikings were probably more concerned with imperial expansion.

Read on for the story of the Viking Crusades.

A Brief Timeline for the Crusades

The First Crusade started in November 1095 when Pope Urban II asked the people of Christendom to go to Jerusalem and “liberate the Church of God” from Muslim control.

He also saw this as an opportunity to direct the energies of the Christian knights who were occupied with infighting and the exploitation of the weak.

In return, the knights would be forgiven for their confessed sins, paving the way to heaven.

The crusades battled their way from Constantinople to Jerusalem, which they eventually captured in June 1099.

Following the conquest, many of the knights decided to return home, leaving just 300 there to defend their conquest.

The military men who remained, including the Templars who were officially formed in 1119, built castles and strongholds across the region.

They were joined by Frankish settlers, who became the rulers of the area but managed to live relatively peacefully with the Muslim locals.

In 1144, under Zengo, the Muslim ruler of Aleppo and Mosul, the Muslims were able to strike back and regain territory, including the Frankish capital of Edessa.

This led the new Pope Eugenius III to call for the Second Crusade, which lasted from 1145 to 1149.

It was fairly disastrous for the knights, but the Franks managed to hold onto Jerusalem until 1187 when a combined force of warriors from Egypt, Syria, and Iraq under Saladin took Jerusalem.

This caused outrage in Europe, and Pope Urban III apparently died upon hearing the news.

Pope Gregory VIII called for the Third Crusade, from 1189-1192.

This is the Crusade that Richard the Lionheart of England, or Robin Hood fame, led.

They laid siege to Acre from 1189 to 1191, and when they captured the city, they killed 2,500 Muslim prisoners.

The Crusaders reached Jerusalem in 1192, but rather than attacking the city, they signed the Treaty of Jaffa that recognized Muslim control over Jerusalem but allowed Christian pilgrims to travel safely through the Holy Land.

Conflict in the region would continue. A Fourth Crusade was called in 1202, and those Crusaders would sack the Christian city of Constantinople.

In 1212 the Children’s Crusade would begin, called this because it was never officially approved by the Pope.

In 1215 there was the Fifth Crusade, in 1228 the Sixth Crusade, in 1248 the Seventh Crusade, in 1270 the Eighth Crusade.

The Crusades would officially end in 1291 when the Christians lost control of all their territory in the Holy Land.

Viking Crusades

The now-Christian Vikings were not among the main knights that led the assault on the Holy Land.

But the Vikings would find themselves in Jerusalem during what is sometimes called the Norwegian Crusades.

They were also encouraged by the Pope to participate in other types of crusades, often called the Northern Crusades.

The Norwegian Crusade

The Norwegian King Sigurd I would lead what was either a pilgrimage or a crusade of Christian Norwegian warriors to the Holy Land between 1107 and 1111, between the First and Second Crusades.

They reportedly had 60 ships and 5,000 men.

The group of warriors first landed in England in 1107 where they spent the winter. In spring 1108 they were in Galicia in Spain where the local lord of Santiago de Compostela initially said they could stay for the winter but then refused to share food with the Norwegians when it ran scarce.

Sigurd attacked the castle and looted it in true Viking style.

The Vikings then moved into Portugal, capturing eight Saracen galleys and the castle at Sintra before reaching Lisbon, where they attacked the half-Christian half-Muslim city.

They then defeated a Muslim squadron to pass the Straits of Gibraltar and enter the Mediterranean.

In 1109, the Vikings attacked the Balearic Islands, which were labeled Islamic but were little more than a pirate haven and slaving center.

They finally reached the Holy Land in 1110, landing at Acre and then meeting the Christian ruler of Jerusalem, King Baldwin I.

They were reportedly welcomed warmly and received treasures such as a splinter of the True Cross.

They then helped Baldwin siege and conquer the Syrian town of Sidon.

They then left the Holy Land, sailing to Constantinople where Sigurd abandoned many of his ships and men before making his way back to Norway overland.

The men left behind seem to have joined the Varangian Guard of the Byzantine Emperor, which was an elite fighting force and bodyguard of the emperor made up of Norsemen and Keivan Rus.

They are famous for their role in the Battle of Beroia in 1122 which saw the Bulgarian people known as the Pecheneg annihilated.

The Varangians also played an important role in defending Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade at the start of the 13th century, although the city would fall.

The Northern Crusades

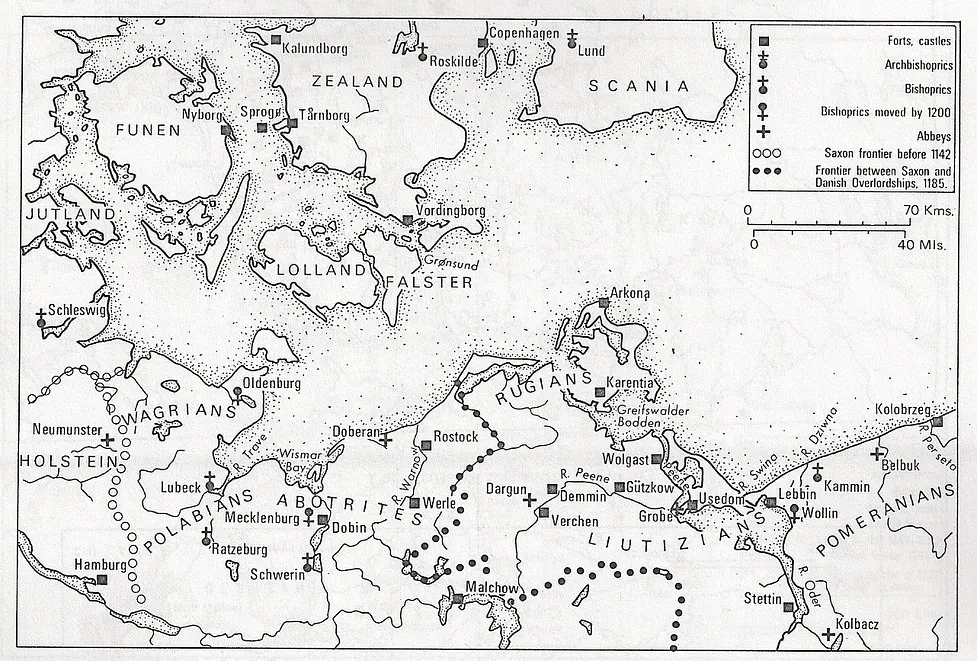

When Pope Eugenius III called the Second Crusade while the knights of France and Germany were sent against the Turks, the Norsemen were encouraged to campaign against the Pagan Wends in the southern Baltic region.

The Wends were Slavic people who occupied modern-day northeast Germany. The Danes were quick to agree since they had been dealing with Wendish pirates for decades.

While the Wendish Crusade officially started in 1144, the Danes had their first major success in 1159 under the Danish king Valdemar the Great. Partnering with the Saxon Duke Henry the Lion, the Saxons attacked the Wendish Island of Rugen by land while the Danes attacked by sea.

They launched similarly successful combined attacks in 1160 and 1164.

However, after this, the alliance broke down and the Danes continued on their own.

They used Viking tactics, using raiding parties to make surprise landings from their longships sweeping quickly inland to plunder, and then returning to their ships before the Wends could organize a defense.

But each longship also carried four fully armored horsemen to join the attacks.

Rather than attack the fortified Wendish towns, they burned crops and villages, taking livestock and captives, and attacking Wendish merchant ships.

These tactics were both effective and profitable.

The Danes could use this money to construct forts at strategic locations on the Danish coast to prevent counter-naval attacks.

Valdemar was famously joined in battle by Absalon, the bishop of Roskilde, who took great pleasure in destroying the idols of the Wendish gods.

Decisive success came in 1168 when the Danes plundered and destroyed the cliff-top sanctuary of the Wendish high god Svantovit on Rugen.

This caused the locals to surrender and accept baptism. With their new allies from Rugun, the Danes destroyed the pirate stronghold of Dziwnow on the island of Wolin in 1170.

Two years later they would defeat the Wendish fleet in a great sea battle, and the Wends would never venture into Danish waters again.

In 1185, the Danes had won control of the entire Baltic Sea from Rugen in the east to the mouth of the river Vistula.

Rather than settle the area, the Danes kept the Wends in line with punitive raids.

The Livonian Crusade

The Christian Vikings crusaded in the north again when Pope Celestine III called for a crusade against the Livonians, a group of tribes living in what is now Latvia and Estonia, in 1193.

The church wanted to convert the pagans to Catholicism and prevent them from coming under the influence of the Greek Orthodox Church.

While German crusaders including the Sword Brothers and the Teutonic Knights were active in the crusades, so was the Danish king Valdemar II, invading Estonia in 1218.

He landed in Lyndanisse, modern Tallinn, with a fleet of 500 longships.

These ships were considered old-fashioned by this time, and it might be the last time they were used in a major offensive in the Baltic.

The Vikings were already being outcompeted in the Baltic by Germans using slower Cog ships, but Cogs were also more suitable for war.

Valdemar set up camp on a hill called Toompea, which was a strategic battle position but was also believed to be the burial place of the local mythological hero Kalev.

Seeing the fleet, the Estonian leaders agreed to submit and allowed themselves to be baptized.

But this turned out to be a ruse to get the Danes to let their guard down. They attacked the camp a few days later.

This led to the legendary battle of Lyndanisse, which the Danes won.

They then built a castle on Toompea. This would give the city of Tallinn its name, which means “Dane’s castle” in the local tongue. In 1224, a stone cathedral was built near the castle.

They would hold Tallinn until 1346, when Denmark sold Estonia to the Teutonic Knights.

The Swedish Crusades

Sweden was being raided by Estonians from the island of Saaremaa, which is Osel in modern Sweden, the Finns from Karelia in eastern Finland, and the Curonians from modern Latvia.

The Swedes were also raiding these pagan neighbors.

They were also competing for influence in the area with Novgorod, a medieval state that spread from the Gulf of Finland across northern Russia.

The Swedes decided to use the language of the crusades to justify conquest in this region, though their actions were never officially sanctioned by the Church.

According to tradition, the first Swedish Crusade into Norway was led by King Erik IX in 1157.

He brought all of south-west Finland under Swedish control and converted those Finns to Christianity.

However, in a letter to Pope Alexander III not long after, a Swedish bishop complained that the Finns always promise to obey the Christian faith but then turn their backs on it when the armies withdraw.

Consequently, Pope Gregory IX called an official crusade against the Finns in the early 13th century, but the Swedes did not heed the call because they were preoccupied with Novgorod.

They attacked Novgorod in 1240 but were defeated.

The Swedes moved east again in 1248 under Birger Jarl, who conquered the Tavista region of central Finland.

Then in 1292 they conquered Karelia and established a church at Vyborg.

They then engaged in raids and skirmishes with Novgorod for the next 30 years, until the Treaty of Noteborg was signed in 1323, establishing a border between Swedish Finland and Novgorod.

Viking Crusaders ?

While the Crusades were a decidedly Christian venture, the participation of the Norsemen looks much more like Viking-style raids under the Christian banner.

They suggest that while the Vikings may have converted to Christianity, they did not give up their warlike ways and passion for raiding