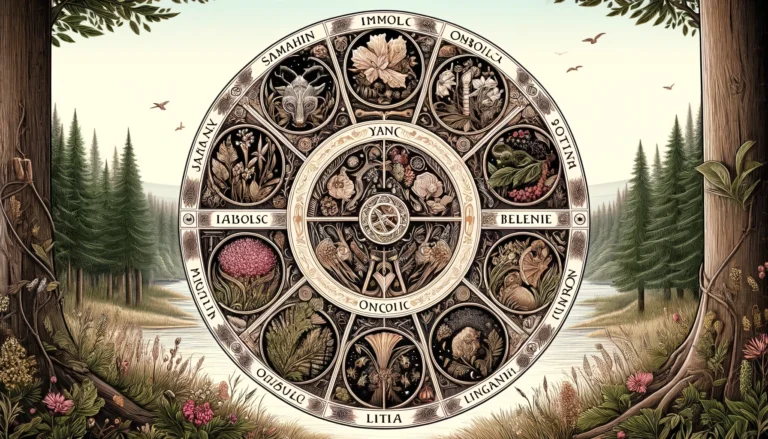

Many modern pagans, and other people who want to create greater alignment with natural cycles, celebrate the Wheel of the Year.

These are festivals that align with important moments in the solar calendar, and therefore the seasons, such as the solstices and equinoxes.

While there are many neo-pagan festivals based on the idea of the Wheel of the Year, there are eight that are almost universally accepted.

Four of these are called fire festivals and are largely inspired by Celtic tradition.

The other four are the solstices and equinoxes, which are more closely related to Germanic tradition or have unknown origins.

Let’s look at the eight festivals that make up the Wheel of the Year.

When do they happen, what was their original significance, and what do we know about how they were celebrated in ancient times?

Remember that the dates given below are all for the northern hemisphere, since the ancient Celts and Germans lived in Europe.

Fire Festivals

The Celts celebrated four fire festivals throughout the year that marked the changing of the seasons.

These seasonal changes were extremely important to the agricultural Celts because it dedicated when to plow, sow, harvest, and rest.

This cycle also reflects birth, death, and rebirth, as does the Triple Goddess, the maiden, mother, and crone, in Celtic and other traditions.

We don’t know exactly when these festivals were created, but there is evidence that they have been marked in the Celtic world for at least 2,000 years.

The dates below are approximate, since the calendar has changed a lot in the last two millennia.

Much of what we know about these festivals today comes from Irish folklore.

While there are probably connections to what was practiced across the Celtic world in previous centuries, it is challenging to draw firm conclusions.

Samhain – October 31/November 1

Samhain marks the beginning of winter and the beginning of the Celtic calendar.

It was at this time that the ancient Celts brought their animals in from summer grazing and started to prepare for the long winter in their homes and forts.

Pronounced “sow-in”, it was associated with the Celtic god Dagda, who lies with the goddess Morrigan, and together they give birth to the new year.

It was also believed that at this time the gods, dead, and fairies met in the human world because the veil between the worlds is thin.

People were warned to be careful of those they met abroad at this time as it could always be a fairy trick.

The festival was celebrated by the community with customs designed to appease the spirits, honor the dead, and protect the community from otherworldly harm.

It involved lighting bonfires, which had protective and cleansing powers.

It was also a time of feasting, and food offerings were made. Plates of food were often left outside villages to appease wandering spirits.

It was also common to wear costumes, usually made from animal heads and skins.

These disguises were meant to confuse spirits that were abroad in the world of the living, and are the ancient inspiration for modern Halloween costumes.

Because spirits were abroad, this was also an effective time to conduct divination rituals.

Imbolc – February 1

Pronounced “im-bulk”, this festival marked the beginning of spring.

The fertility festival was linked with the goddess Brigit and it was common to create Brigit crosses from rushes and straw and hang them around the home for protection.

It was believed that Brigit passed over households and gave her blessing to any home with the symbol.

Imbolc means “in the belly” and references the pregnancy of ewes that signals the beginning of lambing season and renewal of life after winter.

The festival was associated with fertility, purification, and the reawakening of the earth.

As well as the obligatory bonfires and feasts, this was a time for spring cleaning.

It was a way to both physically and metaphorically sweep out the old and make room for new blessings.

Beltane – May 1

Beltane, pronounced “be-yowel-ten-ah”, marks the start of summer and is associated with fertility and growth.

The festival was an invocation for a prosperous season and protection from harm.

Marking the opposite end of the year to Samhain, it was believed that this was another time when the veil between the worlds was thin.

The Celts would do things such as drive cattle between ritual bonfires to purify and protect them before leading them to summer pastures.

This ritual may also have been effective at killing ticks and diseases through the heat and smoke.

Beltane also saw Maypole dancing, intertwining ribbons as a way of symbolizing unity within the community.

Everything was decorated with green branches and flowers to symbolize fertility and new growth, and people would often wear garlands of spring flowers.

Lughnasadh – August 1

Lughnasadh, pronounced “loo-na-saa”, honors the Celtic god Lugh and is an early grain harvest festival.

It is said that Lugh started the festival as a funeral feast and athletic competition (known as Lugh Games) to honor his foster mother Tailtiu, who died of exhaustion after clearing the plains of Ireland for agriculture.

As you might expect, the festival included athletic competitions including horse racing, archery, and wrestling.

It was also a time of communal work as people came together to share the burden of gathering crops. The first fruits of the labor were given over to the communal meal.

Lawsuits were often brought at this time, to be dealt with after the work of the harvest. It was also a popular time of year for matchmaking and joinings.

Equinoxes and Solstices

While the fire festivals happened at the midpoint between the equinoxes and solstices, many modern pagans also celebrate these astronomical events.

However, these celebrations are not Celtic in origin and are borrowed from other traditions, including Germanic.

Nevertheless, they form an important part of the modern Wheel of the Year.

Yule – December 20-23

Yule falls on the winter solstice and marks the shortest day of the year.

It was predominantly a Germanic and Norse festival and many modern Yule traditions can be traced to Norse traditions.

Read our full article on Viking Yule.

Similar to Samhain, the Vikings believed that the veil between the worlds was thin at the time and that the gods crossed over into the human realm.

Odin led the great hunt, and anyone caught outdoors when it passed overhead could be swept up and disappear.

Ostara – March 20-23

Ostara, also known as Eostre, is the spring equinox and is named for a West Germanic goddess of spring.

Ancient traditions and Christian Easter traditions are now so intertwined that it is difficult to separate the two.

For modern pagans the festival is about finding balance between mind, body, and spirit.

It is also a time for cleansing the old to make space for the new, much like Imbolc.

Litha – June 20-23

Litha falls on the summer solstice. Its origins are unclear and is usually described as a festival common among ancient agrarian cultures to mark the longest day of the year.

In most traditions, bonfires play a role, as does jumping over the fire for good luck.

While it celebrates the sun being at its greatest strength it is also a moment of change, as it marks the beginning of the decline of the sun’s energy.

While its origins are unclear, it is arguably the most important festival among modern pagans.

Neo-druidic groups often gather at Stonehenge on this date.

Mabon – September 20-23

Mabon is the autumn equinox and is a festival of thanksgiving for the fruits of the earth.

It also recognizes the need to share those fruits with others to have the favor of the gods during the coming winter months.

Embracing Natural Cycles

While there is not a lot of evidence to describe exactly how ancient Celtic and Germanic tribes celebrated these festivals, we do know that they were important to the community.

Living close to nature, people had to change with nature.

Without modern heating, it was not possible to live the same way in summer and in winter.

Therefore, every season had a distinctive purpose and atmosphere, it makes sense that festivals would be tied to that.

Today many people seek to live in greater alignment with the natural world, like our ancestors did.

There are many ways we can do this in our day to day lives.

This can still be seen in more northerly countries, such as in Scandinavia, where there is a marked difference between the seasons.

You see modern norsemen embracing long holidays in the summer to make the most of the long days and settling into a cozy state of Hygge in the winter months.