Norse accounts of death and the Viking afterlife are quite difficult to unravel.

As death is the ultimate unknown, inconsistency is expected, and all written accounts come from the post-Christian era, and seem to have been influenced by Christian ideas of death.

Vikings did believe in an afterlife, as Norse burial practices were clearly designed to ensure that the deceased had everything they need to thrive after death. Valhalla, Hel, Ran…..and many more.

Funerary Practices of the Vikings

The most common funerary practices among the Vikings were cremation (with the cremated remains then buried) or burial. Viking burials typically included funerary goods alongside the deceased, suggesting a belief that they would need these things in some afterlife.

Viking were buried with possessions that reflected their lives: tools of their profession, jewelry that showed their status, and could also be used as emergency currency (the Vikings often chipped pieces off their precious metal jewelry to act as currency), and warriors with weapons.

Very wealthy Vikings might be buried in a ship that they could use in the afterlife, or stone outlines designed to represent ships, that also seemed fit for purpose.

There is also strong evidence to suggest that the very, very wealthy could have been buried with slaves. A Norse burial site in Flakstad, Norway, contains multiple bodies in the same grave, but DNA and diet suggest that the majority were slaves.

The 10th century traveller Ahmed ibn Fadlan also claims that he saw a woman sacrificed as part of the funeral of a Viking chief. But most Vikings would have had a significantly more modest send off.

For more information read our previous blog post on Viking Funerals.

Realms of the Dead in Norse Mythology

While most of us are familiar with Valhalla, this is only a small part of the wider Norse beliefs about the afterlife.

Norse mythology suggests that a person was composed of four parts: Hamr, physical appearance; Hugr, personality or character; Flygja, totem or familiar spirit; and Hamingja, quality or inherent success in life. While one’s Hamr passes from this world (or at least hopefully, no one wanted to come back as a Draugr), it was probably their Hugr that moved onto the afterlife, while their Hamingja might continue within their family, explaining the Norse practice of describing men as reincarnations of the ancestors.

According to Norse mythology, there were several different afterlife realms where the Hugr element of the soul might find itself.

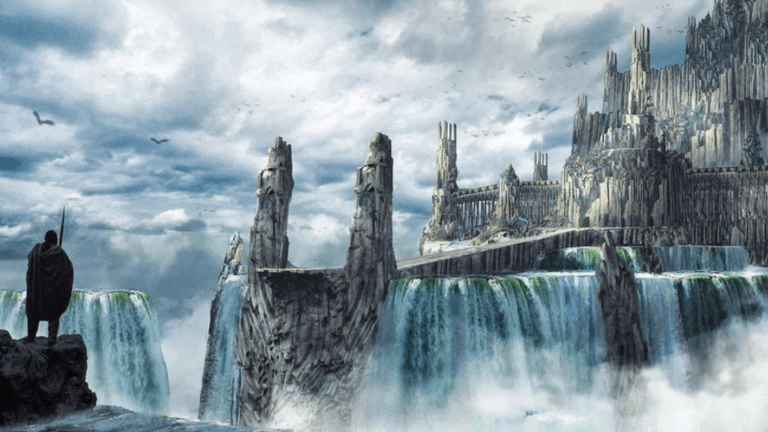

Valhalla

By far the most famous land of the dead, Valhalla was thought to be a great hall in Asgard, the realm of the Norse gods. This hall belonged to Odin, king of the Norse gods and god on war and wisdom.

With the assistance of the Valkyries, Odin chose half the fallen heroes from the battlefield to come and live in Valhalla.

There the dead heroes would feast and fight until the arrival of Ragnarok, the end of the world, when they would fight along Odin and the other Norse gods in the final battle. Only warriors who died in battle could be taken to Valhalla.

Folkvangr

The realm of the goddess Freya, a Norse goddess of fertility and magic, she also took fallen famous Viking warriors from the battlefield, but she got first choice, so presumably the choicest warriors found themselves here.

Although less famous, Folkvangr is arguably a more prestigious afterlife destination for a Viking warrior than Valhalla.

Probably, like the dead of Valhalla, they were destined to fight alongside the Norse gods during Ragnarok.

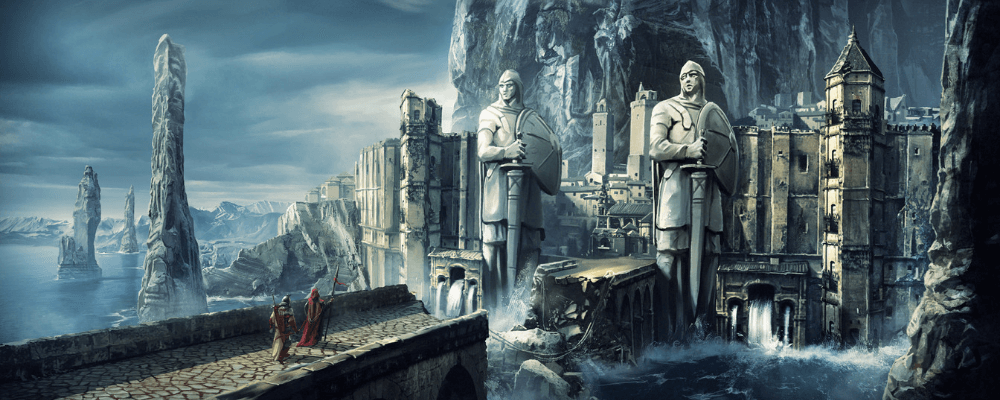

Helheim

According to Norse mythology, Vikings that did not fall in battle would likely find themselves in Helheim, a world beneath Midgard in the cosmology of Norse mythology, ruled over by the goddess Hel.

This realm of death is parted from the realm of the living by a rapid river that cannot be crossed, and heavy gates. Once a soul passes into Helheim it cannot return.

Helheim should not be conflated with Christian ideas of Hell. It was not a place for the wicked, but an afterlife for anyone who did not die in battle.

Even the beloved god Baldr, son or Odin, found himself in Helheim (and not Valhalla) when he was killed in a prank orchestrated by Loki. Not even Odin, king of the Norse gods, could bring him back from the dead, only Hel, the Norse goddess of the underworld, could bestow this gift.

The story of Baldr is interesting in how it suggests that even the Norse gods did not have power over death, which was final. This is also alluded to in the Ragnarok myth which foretells the final death of Odin and the majority of the Norse gods.

The Viking sagas often tell of warrior cutting themselves with blades on their death beads in order to try and trick Hel into thinking that they had died in battle.

If Norse mythology did have an equivalent of Christian Hell, it would have been a place within Helheim called Nastrond, which was said to be a realm of darkness and horror for the wicked.

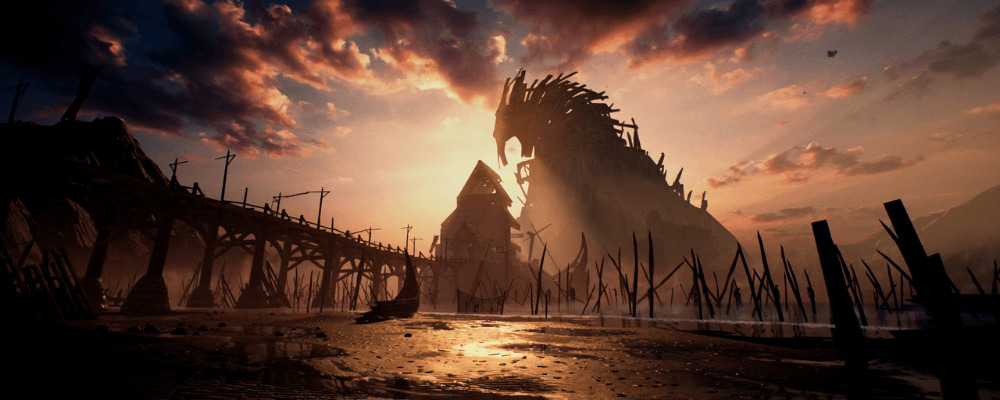

Ran

Considering the seafaring nature of Viking life, it is not surprising that they had an afterlife specifically for sailors.

Ran was a giantess that lived at the bottom of the ocean in a realm illuminated by the masses of treasure that she accumulated from sinking and taking the treasure of passing ships. She would also catch sailors in her nets, drowning them, and then keeping them there in her own watery afterlife.

Helgafjell

Some stories from Norse mythology also suggest that the dead could end up in Helgafjell, the holy mountain, which may have been a specific place, or simply a mountain in the vicinity.

The dead there are described as leading a life pretty similar to the living, reunited with their families and their loved ones. Some living people could see into this mountain afterlife, and what they saw was not intimidating, but a scene of home and happiness.

Christian Influence

Since all written accounts of the Norse afterlife come from post-Christian sources, it is difficult to know how much they have been influenced by Christian ideas of life after death and how much is from the traditional, oral Norse mythology.

For example, it is very difficult to distinguish between Valhalla, Folkvangr and Helheim, as they are rarely named, so it is conceivable that they are simply three different names for the same place, or names for places within a more unified afterlife.

It is the thirteenth century Christian scholar Snorri Sturluson that suggests that warriors go to Valhalla and that the other fallen find themselves in Helheim, dividing the afterlife into a Heaven and Hell more familiar in Christian beliefs.

Whatever the details of what the Viking believed, they did believe in life after death.