We know that Viking culture had sacred spaces to worship their gods because they are mentioned in the surviving sagas and sources. But very little specific detail survives.

We must piece together what these spaces might have been like from descriptions in texts written in Christian times, descriptions of the cult practices of earlier related Germanic tribes, and scant surviving archaeological remains.

Based on what does survive, let’s talk about what sacred spaces looked like in the Viking world.

Natural Sacred Spaces

The Vikings believed that the gods were present in nature, and therefore it was while close to nature, and outside the constructs of human society, that a person could get closest to the gods.

Many natural spaces in the Viking world were named for the gods. We often encounter places with names that mean “Odin’s Meadow”, “Thor’s Grove”, or “Freyr’s Cornfield”.

The sources mention that the Vikings in Dublin had a grove of huge oaks that they called Thor’s Grove, which was burned down by Brian Boruma following his defeat of the Vikings there.

The Byzantines observed that the Varangian traders, who were of Swedish descent, made offerings of birds on an island where a giant oak tree grows.

We know a little bit more about one such space in Iceland from the Eyrbyggja Saga. It mentions a place in West Iceland called Helgafell, located on the peninsula of Snaefellsnes. The space, on top of a hill, was kept completely free of dangerous hazards, and no violence could be committed there, or blood spilled.

The chief, Thorolf, expressed the belief that his family would pass through this particular sacred space on their way to the afterlife. This suggests that it was also considered one of those places where the veil between the worlds was thin and supernatural beings could pass.

There are stories of places where deceased ancestors could pass through from the other worlds to their former homes. They could cause trouble, by killing livestock and burning down homes, or they could visit their loved ones. Though this usually ended in further heartbreak in the sagas.

That the Vikings chose to worship in nature reflects what we know of many earlier Germanic tribes. Greek and Latin authors observed that the Germans considered various woods and groves sacred. The Roman author Tacitus specifically states that the Germans did not build temples or worship idols but conducted their rituals in nature.

Further definitive evidence of this type of worship comes from the fact that early Christian legal codes from Norway and Sweden specifically prohibit the conduct of rituals on mounds, in grooves, woods, and by stones. This seems like a clear attempt to suppress traditional Norse religious activities.

Delineated Sacred Spaces

While much Viking religious activity took place in nature, the Vikings also had methods for delineating sacred spaces within their communities for ritual purposes. These were not permanent spaces but rather set up temporarily for important festivals and other occasions that required the approval of the gods, such as the meeting of the Thing or the law courts.

These created sacred spaces were called Fridgardr, which means peace enclosure. One of the important elements is that it is a delineated and protected space, like Asgard and Midgard, rather than a chaotic space, like Jotunheim and Vanaheim.

According to descriptions, the spaces were delineated by wooden poles and ropes. These are temporary structures, which reflects the fact that these delineated structures were temporary. They might be set up in a farmhouse, long hall, or other large building for an important festival, but also for a legal trial or a duel, which was also considered a semi-sacred activity.

When a space was designated for sacred activities, the Vikings would have called on the gods to hallow the space. This was one of the functions of Thor’s hammer Mjolnir, and he may have been the principal god invoked to protect a temporary sacred space.

There is good evidence for these types of spaces in Iceland, where many places were called a Hof, which refers to a sacred space. The working theory is that areas on certain farms were delineated in this way for ritual or community purposes, but over time the entire farmstead became known by this name. Archaeological evidence does not suggest the presence of many permanent sacred spaces across Iceland or Scandinavia.

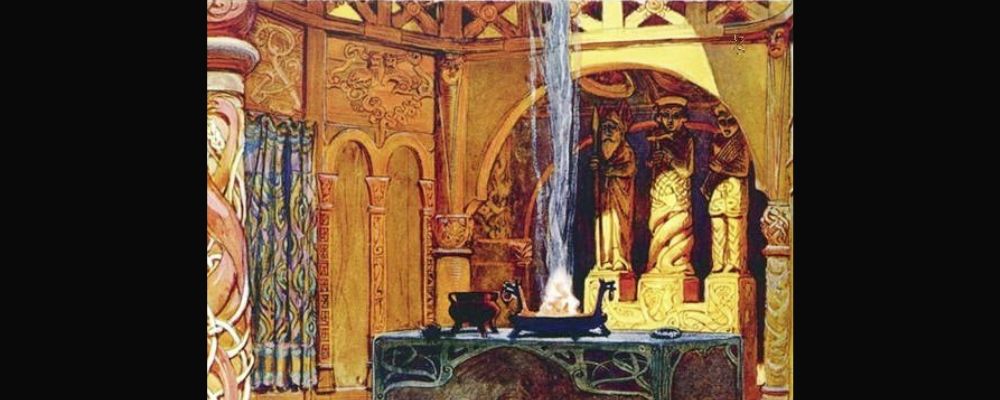

The Eyrbyggja Saga gives a description of this type of building. It suggests that when it was used for religious purposes a high seat was placed near the entrance and held in place by “divine nails”.

An altar was placed in the middle of the room on which was set an unbroken golden arm ring weighing 22 ounces which men would swear oaths on. Also in the middle of the room was a bowl of sacrificial blood, collected when an animal was sacrificed, and a twig called a hlaut that was used for the spreading of blood. Images of the gods were placed around the building.

Snorri Sturluson describes a similar arrangement at Trondheim in Norway. He notes that the leaders that met for festivals were required to bring enough food for the festival and enough animals to meet sacrificial demands.

The blood of sacrificed animals was collected in bowls and sprinkled around the space. The meat of the animals was cooked in the center of the room and everyone would sit around the cooking meat to eat.

He describes statues of the gods placed around the temple and toasts made to Odin for victory and success, Njord, presumably for fortune and safety at sea, and Freyr for a good harvest and peace.

As societies became more organized and communities grew, it is possible that sacred spaces became permanent as they were needed more often. There is evidence of a relatively permanent sacred space, called a Ve, at Jelling in Denmark dating to the rule of Gorm the Old in the 10th century.

Archaeological remains reveal a wooden building with a clay floor and a single massive roof post in the middle. The structure was destroyed and replaced with a church. This was a common practice during the Christian conversion.

Temple at Uppsala

While permanent temples appear to have been quite rare in the Viking world, the surviving sources suggest that there was quite a famous one at Uppsala in Sweden, and perhaps also at Maere in Norway.

At Uppsala, a group of ancient wooden buildings has been found beneath a Medieval church. This is the sacred space that features in the TV show Vikings.

It is described as being of similar size and grandeur as Greco-Roman temples. But it is worth remembering that the Christian authors who described it were familiar with these temples and may have used them as a “template” for pagan worship.

The Anglo-Saxon writer Adam of Bremen describes the temple as built around an evergreen tree with wide extending branches, which sits beside a fresh spring. The area of the temple was delineated by a gold chain, and so much gold was used to decorate the wooden temple that it glistened from afar. He says that there were three statues of the gods inside the temple. Thor sits in the middle with Odin and Freyr on either side.

Wooden stave churches that were popular in Norway and Sweden between the 11th and 13th centuries when the Vikings there first converted to Christianity may be further examples of what wooden pagan temples looked like. These are quite distinct from the brick churches seen in England and Germany and may borrow from earlier religious architecture.

The remains of 31 such wooden churches survive with elaborately carved doors and walls using traditional Norse artistic design styles. The churches often had gargoyles on pillars inside, and dragon heads adorning the outside of the temples, not too different from the dragon heads that were used to decorate Viking ships.

One such stave church, from Heddal in Norway, seems to be specifically linked with the old religion through its foundation story, which closely matches the story of the building of the walls of Asgard.

In the story of the gods, an unknown giant turns up and offers to build the walls of Asgard. He agrees to build the walls for the sun, moon, and hand of Freyja in marriage, which the gods agree to pay if he can finish the work within an impossible timeline. When it seems that the giant will complete his work, they sabotage him so that they will not have to pay, and then kill him.

In the story of the church at Haddel, five local farmers decide to build the church. One of them meets a stranger who agrees to build the church, but in payment, the farmer must either fetch the sun and moon from the sky, forfeit his life’s blood, or guess the builder’s name. The farmer agrees, thinking that he will have plenty of time to figure out the man’s name.

The builder completes the work unbelievably quickly, in just three days. The farmer becomes very nervous. But on the day that he must meet the builder he overhears a voice bragging that he will soon be in possession of the sun and the moon, and referring to himself by his own name, Finn. As such, the farmer knows the name of the builder and the problem is resolved. No one seems to have been killed in this particular tale, though the builder moved away because he could not stand the sound of the church bells.

Sacred Spaces in the Viking World

The idea of dedicated sacred buildings seems quite alien in the Viking world. While they would have known about this practice from Greco-Roman examples and Christian churches, they seem to have believed that the gods were everywhere and that the best places to connect with the gods were locations in nature where the veil between the worlds was at its thinnest.

When they did need sacred spaces within the community for important festivals or gatherings, they created them on a temporary basis by demarking a protected space and calling on the gods to hallow the space.

As society became more complex and was no doubt influenced by the Christian world, more permanent sacred buildings seem to have developed.While Thor’s hammer was often called on to hallow sacred spaces, it was also used by the Vikings as a symbol of allegiance to the gods and protection. Why not check out some of the Mjolnir / Thor’s Hammer pieces in the VKNG collection.