There is good evidence that the Vikings were sailing into the Baltic and the region of Estonia from the start of the 9th century and that by the 10th century, they were having a big impact on the area with several Estonian-Viking settlements emerging in the mostly Finno-Hungarian region.

However new archaeological evidence suggests that their presence in Estonia was much older, potentially starting in the 7th century.

If this is true, it might also push the dawn of the Viking Age back around a hundred years from its current start date, usually accepted as 793 when the Vikings raided Lindisfarne in England.

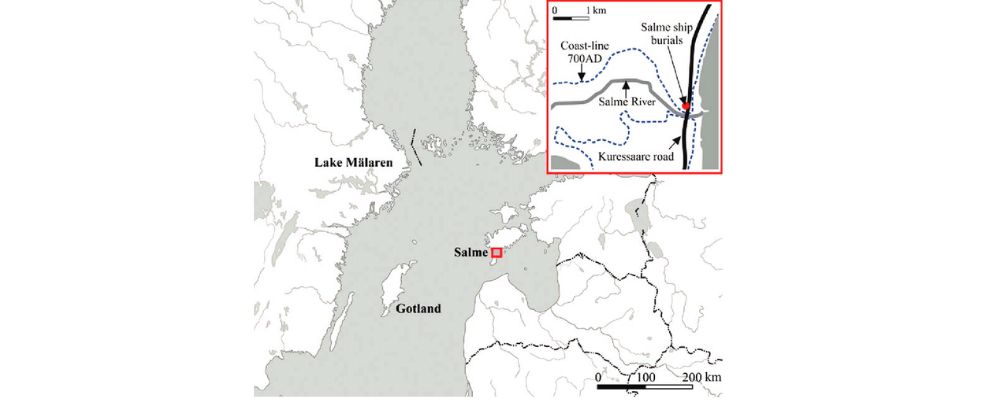

This new evidence, two ships discovered at Salme on the Estonian island of Saaremaa, also reveals what Viking raiding parties might have looked like.

King Ingvar Harra of Sweden

In the 12th century, the Icelandic Christian historian Snorri Sturluson wrote the Ynglinga saga.

It is supposed to tell the earliest history of the Swedish kings but is considered mostly myth and legend.

Among other things, it says that the god Freyr founded the first Swedish dynasty, the Yngling dynasty, at Uppsala. But that doesn’t mean that it doesn’t contain any real history.

According to the saga, in the 7th century King Ingvar Harra, the son of Osten, spent much of his time patrolling the shores of Sweden to protect them from Danish and Estonian raiders.

Eventually, he made a treaty with the Danes that allowed him to focus his efforts and dealing with the Estonians and seeking retribution.

One summer, he sailed to a place in Estonia called Stein, either to raid or negotiate with the Estonians.

But they were ready for him and assembled a great army.

In the ensuing battle, King Ingvar was killed, and his men were forced to retreat. According to Sturluson, the king was buried in Estonia on the shores of Adalsysla on mainland Estonia.

But Sturluson also quotes a 9th-century Old Norse poem that confirms the death of Yngvar in Estonia but says that he was buried on an island in the heart of the Baltic where the sea sings songs of the sea giant Gymir to delight the Swedish ruler.

The 13th-century Historia Norwegiae, written in Latin by an anonymous monk, confirms the poem, saying that he was buried on an island in the Baltic called Eysysla, which is the Old Norse name for the island of Saaremaa.

The Salme Ship Discoveries

In 2008, archaeologists discovered the remains of a ship 11.5 meters long and two meters wide with six bodies inside at Salme on the island of Saaremaa.

Initially, they thought that these were unlucky WWII soldiers, but they were later believed to be Viking remains.

While this was already an incredible find, things became even more interesting when a second ship, 17 meters long and three meters wide, was discovered in 2010 just 100 feet the first boat containing the remains of 33 Viking warriors.

Archaeologists believe that there is evidence that one more ship may still be discovered on the island.

Of course, the wood had completely rotted away over the more than 1,000 years that the ships were waiting to be discovered.

But the smaller ship was reconstructed from discoloration caused by the wood and 275 iron rivets.

The second ship left behind more than 1,200 nails and rivets.

The nature of the artifacts and DNA analysis of the remains suggest that the men, and they were all men, buried on the ships came from Sweden.

Radiocarbon dating and archaeological analysis suggest that the ships were originally built sometime between 650-700, patched and repaired for continuous use over decades, and found their final resting place between 700-750.

The evidence also suggests that these ships used sails, which is the earliest evidence of the use of sails by the Vikings and in the Baltic.

But this would explain how the ships were able to navigate the 100 miles of open sea between Sweden and Estonia.

It also suggests that the Vikings were using their superior ship technology to dominate their neighbors 50-100 years before they conducted the famous raid at Lindisfarne in England.

Who Was Found on the Boats?

The men buried on these boats were Vikings from Sweden.

They seem to have been a raiding party as they were all between the ages of 18-45, and many showed signs of wounds that had healed, suggesting that they were veterans.

The number of swords, shields, spearheads, arrowheads, and knives found among the remains also suggests a group of warriors.

Interesting, they seem to have been a robust group. The average height was 5’10”, which was tall even for Vikings.

They would have towered over the French and English neighbors who were only around 5’5”.

Plus, a couple of the warriors were more than six feet tall ! DNA evidence suggests that four of the men were brothers, and they were related to one more man, perhaps an uncle.

Buried alongside the warriors were six dogs, who seem to have been ritually slaughtered, and two hunting hawks.

Burial Practices

While the boats were clearly warships, they ended up being graves.

While bearing individuals in ships was a common Viking practice, they were usually for only one or two people.

Plus, the Salme ships predate the first known ship burial by around 100 years.

The larger of the two ships was organized as a mass grave.

A group of 33 warriors were neatly lined up in four layers and covered in a dome of shields, which then seemed to have been covered with the ship’s sail as a kind of shroud.

This may then have been covered by sand.

The men were buried with grave goods, including their weapons and other items such as combs and gaming pieces (more than 100 were found), suggesting that they were deliberately prepared to pass into the next life.

There was also a clear hierarchy within the burial, and it seems that the men on the bottom of the pile were the lowest ranking while the men near the top were the highest as they had the finest weapons.

At the top was a man with a jeweled sword hilt and the finest blade on the ship.

He was also buried with an elaborately carved walrus-ivory gaming piece in his mouth.

This may have been the equivalent of the king piece, and an indication of his status in this mass burial.

There were a few other blades near the top that were made from iron and of better quality than the rest.

This suggests that the warriors were led by a king or chieftain with the help of some lieutenants.

The six bodies on the smaller ship were not organized in the same way.

They were slumped individually or in pairs, suggesting that they died where they sat.

Their bodies were not prepared for burial, and everything was left more or less where it lay.

So, What Happened?

It seems clear that the men aboard these ships were a party of warriors.

Whether they were on their own or part of a larger force is unclear.

Their ships were attacked, as evidenced by numerous arrowheads that would have been embedded in the ship, including three-pointed types that were used to carry burning materials to set ships alight.

They seem to have pulled the ships ashore to create a defensive perimeter.

This is suggested by evidence that some of the men died in hand combat with wounds on their arms where they would have raised them in defense.

When the fighting was over, the six men found on the smaller ship must have arranged the burial of those who had died in battle and then sought shelter in the smaller ship where they died of their wounds or starvation.

They must have lost the battle for the survivors to have been left behind to die in this way.

Over time both ships were covered by sand and vegetation and were forgotten.

Is the man with the king in his mouth King Ingvar from legend ?

If it is, it would certainly tie in conveniently with the surviving written sources. It would suggest that he and his men were buried on the island that the Vikings called Eysysla. But while this would certainly tie up loose ends, there is no way to confirm this theory.