If you are a student of Viking history or Norse mythology then you have probably come across the name Snorri Sturluson. He is one of our main sources for both the legendary stories of the gods and the histories of the Norwegian kings.

But considering just how important Snorri Sturluson is as a source, it is important to know who he is and why he chose to write his books. The cultural context of the author and what they hoped to achieve with their writing guide us in terms of how accurate we believe their accounts to be and how certain elements are interpreted.

With that in mind, let’s take a closer look at the life, works, and motivations of our more important written source for the Viking age.

Snorri Sturluson Genealogy

Snorri Sturluson was born in Iceland in 1179; Iceland was considered a Christian country from the year 1000. He was the son of Sturla Thordason the Elder, from Hvammur i Dolun, and was part of a wealthy Icelandic family. He had at least four siblings and nine half-siblings.

According to the Landnamabok, which was written by Snorri Sturluson’s cousin, the family had respectable Christian and Pagan roots.

His father traced his line back to Helgi the Lean, who arrived in Iceland in 890 but was distinguished from his neighbors as he was already a Christian at this time. On his mother’s side, the family descended from the early Pagan settlers Kveld-Ulf and Skalla-Grim. This meant that the famous writer and hero Egil Skallgrimson was also an ancestor of Snorri Sturluson.

There is some evidence that Snorri Sturluson’s family, while probably not Pagan, were interested in the Old Norse traditions.

His father, Sturla, found himself in a legal dispute with the priest and chieftain Pall Solvason. As the proceedings were underway, Pall’s wife attacked Sturla with a knife. She would later claim that she wanted to leave Sturla with only one eye, like his hero Odin. But she missed and instead slashed his cheek.

Strula would have had the right to claim compensation from Pall and bankrupt the man. Instead, another powerful Icelandic chief, named Jon Loftsson, stepped in and brokered a better deal. As part of this, he agreed to take in and raise Snorri Sturluson.

Jon Loftsson was linked with the Norwegian royal family, so this probably represented a desirable opportunity for the family. Snorri would go to Oddi with Jon Loftsson and never return home.

Snorri Sturluson Biography

Young Snorri Sturluson

Considering Snorri Sturluson’s future career as a writer and poet, he must have received a good education from his foster father, who died when he was just 18 years of age. He studied with Jon Loftsson’s grandfather, the well-known scholar and priest, Saemudr Frodi.

While the lessons he learned at school would help Snorri Sturluson throughout his life, his biography is perhaps best characterized by political intrigue and advantageous marriages.

Snorri Sturluson’s first marriage was to a woman named Herdis, from whom he inherited a large estate in Borg and a local chieftainship. These chief positions are perhaps best interpreted as the position of “lord of the manor”. The pair had at least four children but soon separated because of Snorri’s philandering.

In 1209, Snorri Sturluson settled by himself in Reykholt as an estate manager. There he had another five children with three different mothers.

In 1215, he was elected lawspeaker of the Althing, a very important political position in the Icelandic Commonwealth.

Snorri Struluson and Norwegian Influence

Sturluson left the position in 1218 when he was invited to Norway by the royal family. There he became close to the teenage Norwegian king Hakon Hakonarson and his regent Jarl Skuli. They showered the Icelander with gifts, and in return, he wrote poetry praising their deeds and justifying their rule.

Snorri Struluson returned to Iceland in 1220, probably charged by the Norwegian royal household to help them incorporate Iceland into the Norwegian empire. This is what Snorri Sturluson would advocate when he became lawspeaker again in 1222, a position he would hold for the next ten years. He may have been the most popular politician on the island at this time.

Sturluson tried to replicate the successes of his previous advantageous marriages. He tried to marry Solveig, the granddaughter of his foster father Jon Loftsson, in 1222, but was passed over for his political rival and nephew Sturla Sighvatsson. Instead, he married another granddaughter of Jon Loftsson, Hallveig Ormsdottir, in 1224.

As he tried to consolidate his power in Iceland, possibly hoping to be able to hand the colony to the Norwegian king, he came into armed conflict with his nephew and other rivals on several occasions. Civil unrest in Iceland got so bad that King Hakon IV for Norway invited the chiefs to Norway to resolve their differences. The chiefs accurately saw this as a trap and refused the invitation.

Fall of Snorri Sturluson

Snorri Sturluson was eventually forced out of Iceland and returned to Norway and the protection of his patron in 1237.

But there Snorri Sturluson found himself needing to choose between King Hakon IV and his ex-regent, Jarl Skuli, who would revolt and call himself king in 1240.

Sturluson seems to have chosen the latter. In 1238, when many of his enemies in Iceland had been killed, Sturluson asked to be able to return. King Hakon refused the request, as he felt he could no longer rely on the Icelandic poet, while Jarl Skuli granted it. Snorri would return in 1239.

Not long after Snorri Sturluson returned, King Hakon IV would consolidate his power and kill Jarl Skuli. The assassins that killed Sturluson back in Iceland also claimed to be working for the king.

Snorri Sturluson’s Literary Works

Snorri Struluson is considered to have produced three great literary works that are essential to our knowledge of Viking culture and Norse mythology. These are the Prose Edda, Heimskringla, and Egil’s Saga.

Prose Edda

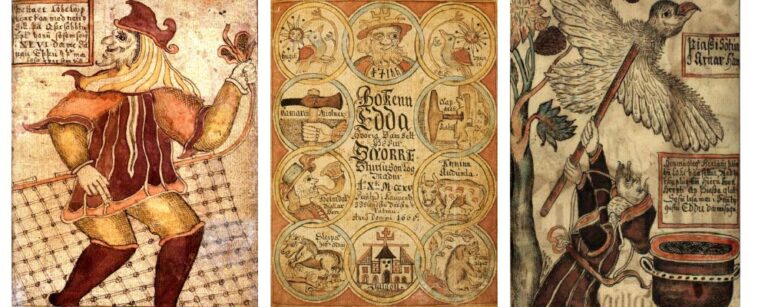

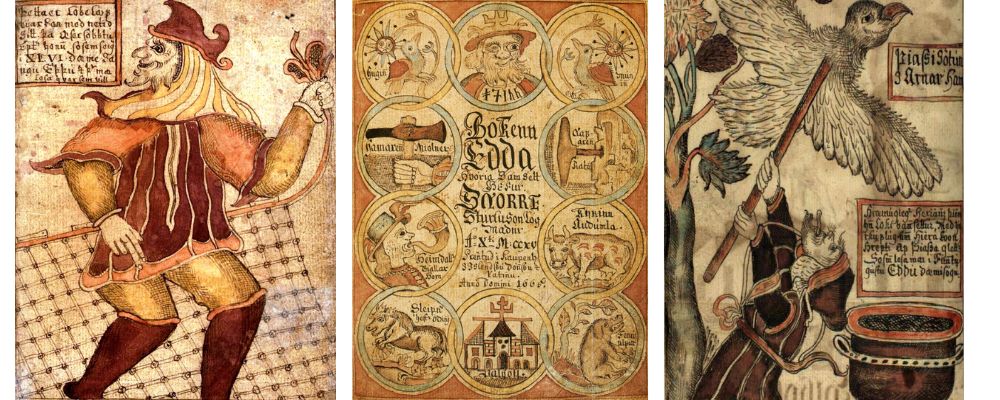

The Prose Edda, and known as the Younger Edda, is the fullest and most detailed surviving source of Norse mythology, even though it was written by a Christian when Iceland had already been a Christian country for two centuries.

While the book addresses Norse mythology, it was actually written by the Icelandic as a guide to Norse poetry. Norse poetry and Skaldic poetry rely heavily on “kennings”, which are figurative metaphors used in place of proper nouns. In Old Norse poetry, they almost always referred to old mythology. This meant that they were almost impossible to understand without a good grounding in that mythology.

Snorri Sturluson’s purpose with the Prose Edda seems to have been to provide that firm basis for poets to draw upon.

The book is composed of four sections.

- The prologue offers a euhemerized account of the Norse gods, linking them to historical people to make sense of the mythology within the Christian religion.

- The Gylfaginning, in which various stories from mythology are retold, in particular those linked to the creation and destruction of the world.

- The Skaldskaparmal reveals more Norse myths and also provides an extensive list of kennings used in existing poetry.

- The Hattatal is a discussion of the composition of traditional Skaldic poetry.

It is believed that Snorry Sturluson drew on both existing written manuscripts and oral traditions retained within the community to compose his stories about the Norse gods and giants. But there is also evidence to suggest that where there were blanks in his stories or things did not wrap up neatly, he invented believable information to fill those gaps.

All of his interpretation of the myths is also colored by the new Christian culture of Iceland. For example, when it comes to Ragnarok, the Norse apocalypse myth, it seems that the 10th-century Voluspa has the story ending with all existence sinking back into the waters of chaos. But Sturluson’s version adds that some of the gods survive to rebuild the world after it re-emerges. This seems like a Christian addition, pulling on the idea of god promising to rebuild the world after the destruction of the flood.

It is worth noting that Snorri’s edda is the only surviving source for some stories from Norse mythology, with no corroborating evidence elsewhere. These include:

- The creation myth

- Building the walls of Asgard and the birth of Sleipnir

- Mead of Poetry

- How Thor got his Hammer

- Thor and Utgard-Loki

- Fenrir and Tyr

- The death of Balder

While these stories probably draw on genuine Norse myths, the details recorded by Sturluson do need to be questioned.

Many scholars point to the fact that Sturluson describes the world coming into existence thanks to a kind of volcanic eruption from Mulspelheim. This seems out of place in old German and Norse myths, since there are no volcanoes in these regions of the world. But they are in Iceland. Farmers in Iceland also relied heavily on cattle, much more so than their Scandinavian ancestors, and Sturluson has a primordial cow eat the ancestor of all the gods out of a salt lick.

Discrepancies with other sources also exist. Struluso includes Odin’s spear Gungnir among the treasures that Loki gets from the dwarves alongside Thor’s hammer Mjolnir, when elsewhere the sources imply that the dwarves made the spear for Odin at his request.

It is also Sturluson who makes Loki the father of many of the creatures in Norse myth including Fenrir, Jormungandr, Hel, and Sleipnir. In this way, he seems to promote Loki to the position of villain in his stories, which is not as well pronounced in other sources.

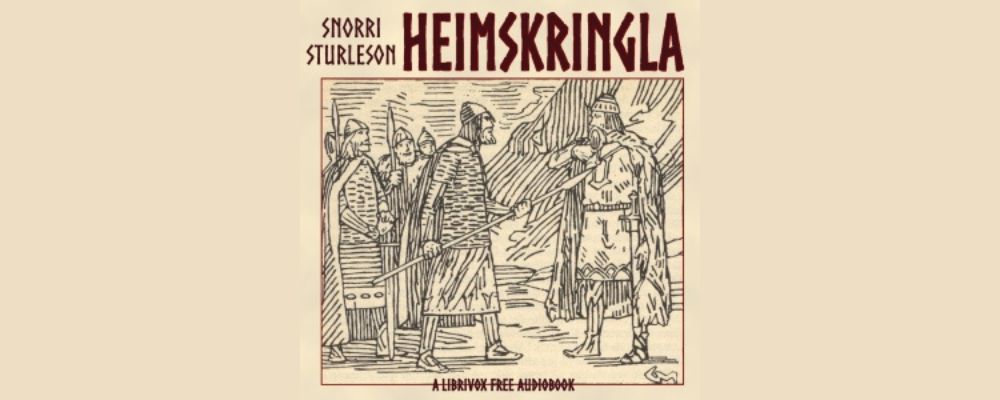

Heimskringla

The Heimskringla is named for the first two words that appear in the manuscript, kringla heimsins, which means circle of the world. The manuscript tells the stories of Swedish and Norwegian kings, no doubt to gratify Struluson’s patrons in the Norwegian royal family.

He starts with the legendary Ynglings dynasty of Sweden, and then tells the stories of historical Norwegian rulers from Harald Fairhair, who united Norway, to Eystein Meylar, considered a pretender and who died two years before Sturluson was born.

All of Sturluson’s characters are larger than life and the historical accuracy questionable. He may also have used the work to influence his patrons by showing them through stories of the qualities of good and bad kings.

But, while stories of witches and warriors able to defeat 100 men single handedly may be embellished, the world is considered an excellent source for customs and culture in 13th-century Norway and Iceland, which Snorri and his readers would have been very familiar with.

Egil’s Saga

It is not confirmed that Snorri Sturluson wrote Egils Saga, but there is good reason to suggest that he is the hand behind the saga about his ancestor. Or at least the first part of it.

The language of the text suggests that it was written in the early 13th century, and Sturluson was the best-known poet and author in Iceland at that time and claimed descent from the hero.

There is a lot of word usage correlation between Sturluson’s account of the Norse kings and the text of Egils Saga. Themes also reappear. But while Sturluson seems to have shown great favor towards the Norse monarchs in the Heimskringla, he is less favorable in Egils Saga, in which he seems to suggest that the heroes of Iceland are a match for the kings.

Scholars suggest that this represents a change in Snorri Sturluson’s own worldview. While he had been an advocate of the Norwegian royals until 1232, his relationship with King Hakon IV had soured by the time he returned to Norway in 1237. Perhaps Egils Saga was an antidote to his previous work.

The last few chapters of Egils Saga feel different from the rest of the composition, leading to the suggestion that it was finished by another hand. This would make sense if Sturluson wrote it near the end of his life, and was assassinated before he could finish it.

Life and Times of Snorri Sturluson

So, that’s what we know about Snorri Sturluson, the Icelandic historian and poet who is our most important source for Viking history and Norse mythology. How do you think his life may have influenced his telling of these important stories?

Considering it is Snorri Sturluson who tells us the tail of how Thor got his hammer, why not check out some of the Mjolnir pendants available in the VKNG Collection.