It is well known that the Vikings originally hailed from the modern Scandinavian countries of Norway, Sweden, and Denmark, all of which were formed in the Viking age when areas ruled by chieftains were consolidated into confederated alliances.

We also know that the Vikings raided around Europe and eventually began to settle in some of their “hunting grounds,” including the British Isles, France, and to the west as far as the Baltic coast.

But not all Viking expansion was the result of war and conquest. The Vikings, especially the Norwegian Vikings, also explored westward into the North Atlantic Sea, where they found uninhabited or lightly inhabited territories that they settled and incorporated into the Norwegian empire.

Let’s look at the Norwegian expansion into the North Atlantic Ocean and their settlement of the Orcades, Iceland, and Greenland.

Start of the Viking Age

The great Viking age started in the 8th century when their ship technology allowed them to travel further from the coasts of their homelands and a strategic advantage over neighbors with faster ships that could sail closer to the coastline and down rivers for surprise attacks.

Among their first targets were the British Isles, wealthy lands just to the southwest of their territory. Not only were their lands highly fertile, but they found communities unprepared for attacks and monasteries hoarding great wealth.

The start of Viking presence in the British Isles is usually dated to 8 June 793, when they raided and destroyed the abbey at Lindisfarne.

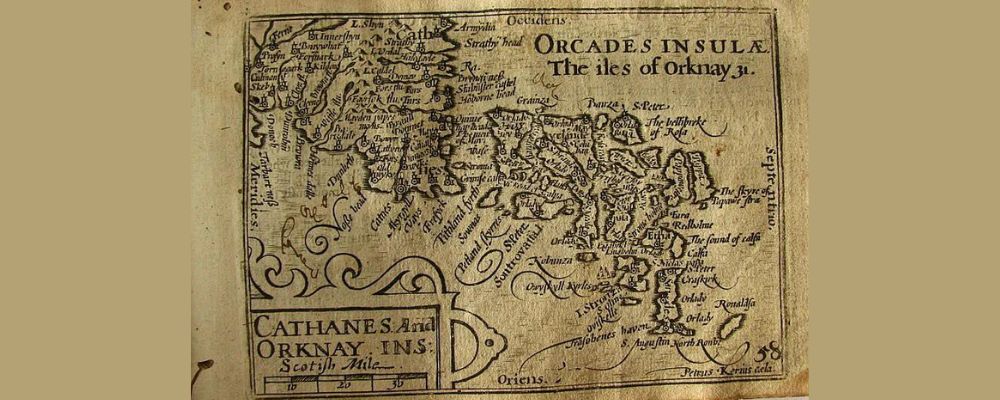

Vikings in the Orcades

It was probably around this time that the Vikings encountered the Orcades. This is the collective name given by the Romans to the islands in the North Atlantic Ocean north of Scotland, including the Orkney Islands, Shetland Islands, and the Hebrides. These all lie on navigational routes between Scandinavia and the British Isles and would have been seen as strategic stop-over points.

The islands were certainly inhabited before the Vikings dropped anchor on their shores, probably by people from the British Isles based on early place names. There is evidence that the islands may have been inhabited from around 8,000 BC, and there is certainly archaeological evidence of settlements from around 4,000-3,000 BC.

The Romans knew about the islands, which they referred to collectively as the Orcades, as they are mentioned in several sources. They were inhabited in AD 43, as the King of the Orcades is listed as one of the 11 British rulers that paid homage to the Roman emperor Claudius following the Roman British conquest.

The islands were still occupied 700 years later at the start of the Viking period, as there is evidence of trade between the Vikings and the locals. But communities seem to have been small.

From around the 8th century, the Vikings no longer seemed satisfied with just stopping off on the islands and trading and began to seed their own communities. This act of colonization overwhelmed the locals. If settlement began in the mid-8th century, by the mid-9th century, the islands had become “Viking-ized”. The local language was a Nordic dialect known as Norn, place names were all Norse, and Viking law dominated the land.

But there is no evidence that the Viking colonization of these islands was particularly bloody. It was probably achieved through intermarriage with local rulers, using force to solve disputes in favor of their local allies, and bringing new wealth and opportunity to the islands.

The main violence associated with the colonization of the North Atlantic islands was between the Vikings themselves. When King Harald Finehair unified Norway under his own rule, many other local rulers were forced to flee, often to the islands. In 875, Harald decided to stamp out potential resistance in the area and gathered a fleet to seize control of the islands. The earldom of Orkney was given to his ally Rognvald, and the area officially became part of the new Norwegian empire.

Vikings in Iceland

The name King Harald Finehair also comes up in the story of the settlement of Iceland by the Norwegian Vikings. This story is recorded in the Landnamabok, Book of Settlements, and the Islendingabok, Book of the Icelanders, both written about 200 years after the fact. Both point to the tyranny of Harald Fairhair as one of the motivating factors behind the Iceland migration.

Iceland was apparently discovered in the mid 9the century when a Norwegian named Naddodr was blown off course on his way to the Faroe Islands. He brought news of the new land back to his people. At around the same time, a Swedish Viking called Gardar Svavarsson might also have found the island and circumnavigated it, and then returned with news.

But there is pretty good evidence that Iceland may already have been occupied at this time. There is good evidence that a group of Hiberno-Scottish monks from Ireland may have settled near Kveverkarhellic cave in around 800. As well as archaeological remains, in 825 an Irish monk called Diciul records that he met monks from the island of Thule, where the winters are pitch black, but it is so light in the summer that you could pick lice off your clothing in the middle of the night.

There is also evidence of a cabin at Hafnir that was abandoned in the 9th century before the date of the Icelandic settlement, but it is unclear whether this was a Scandinavian or British settlement. But even if there were a few settlements spotted around, Iceland was largely unpopulated and therefore represented land that could be settled without conquest.

Viking settlement began in earnest in the 870s. First, Floki Vilgerdarson, one of the inspirations for the character Floki in Vikings, sailed to the island. He took three ravens with him and sent them out to find land to help guide him to the island, earning him the name Hrafna-Floki (Raven Floki). His cattle died not long after landing, and when he saw an ice drift in the fjord near his settlement, he called the land Iceland. Despite his hardships, before long, he returned to Norway to recruit more settlers.

The next main wave of settlement was led by a Norwegian chieftain called Ingolfur Arnarson, who arrived in 874 and formed the settlement of Reykjavik. This kicked off 60 years of fairly intense migration, which started with 300-400 people and peaked with a local population of 4,000-24,000. The surviving sources record that at the height of the Viking settlement, there were 1,500 farms and place names.

Iceland evolved into a Viking community independent of their Norwegian predecessors and it was a stronghold of Viking language and culture for centuries.

Vikings in Greenland

While Iceland enjoyed a more temperate climate in the Viking age than it has today, Greenland was always quite inhospitable, but it nevertheless attracted Viking settlers. The settlement apparently started with Erik the Red, whose hot temper saw him exiled from Iceland for three years. He had probably heard of Greenland from other Viking explorers and decided to try his luck.

While the land was cold, it was possible to rear some cattle and raise some crops. Plus, the region was rich in attractive trade items such as furs, whale blubber, and walrus ivory. Erik returned to Iceland and convinced others to follow him to the new island, which he called Greenland, to make it more attractive to settlers.

Nevertheless, the community was always small, never growing to more than around 2,000 people. But they made significant cultural contributions, including spearheading the Viking discovery of North America.

The community ended at the end of the 14th century when the region suffered a mini–Ice Age, which made the land inhospitable. It seems that by 1408, the original Viking community that moved from Iceland were all gone.

Again, Greenland was not completely unpopulated when the Vikings arrived, but was sparsely populated enough that the Viking settlement of the area was relatively peaceful. Greenland Inuits, related to the Canadian Inuits, seem to have settled on the island around 2500 BC. They were then displaced by the Dorset people, a Paleo-Eskimo community, by around 700 BC. They lived there until around 700, when the Vikings arrived. This may have been what pushed them out of the area, allowing the Thule Inuits to return from Arctic Canada from around 1300. These are the descendants of today’s Greenland Inuits.

Viking Expansion

The story of Viking expansion is not just one of the bloody raids and seizure of territory. The Vikings also took advantage of uninhabited or sparsely populated lands to expand. Part of this may have been a search for political freedom at a time when small earldoms were being consolidated into greater kingdoms, but the rising population and the need for new arable land was probably also a driving factor.If you are a fan of the Viking spirit of risk and adventure, check out the Vegvisir pieces in the VKNG collection. This magical runic stave from the 18th century Icelandic grimoires ensures that you never lose your way, even if you don’t know where you are going.