The Vikings believed in the possibility of revenants, that is the dead returning to wreak havoc on the living.

Among the Vikings, the undead of nightmares were often called draugr or aptrganga, which means “after walkers.”

They are usually described as having blue skin, which was a common indicator of death.

The giantess Hel is described as being half flesh-colored and half blue, which is interpreted as meaning that she was half living and half dead, making her the ideal queen of the underworld.

They also have terrible eyes that could freeze a man in fear.

They lived in their burial mounds and usually came out at night.

They had superhuman powers that allowed them to terrorize the people in the surrounding area, killing livestock, collapsing homes, and murdering people by breaking all the bones in their bodies.

Extended contact with a revenant could send a person mad.

What steps did the Vikings take to prevent people from returning as revenants and deal with them when they did occur? Let’s look at the evidence from the sagas and Viking burial archaeology.

Moving Between Realms

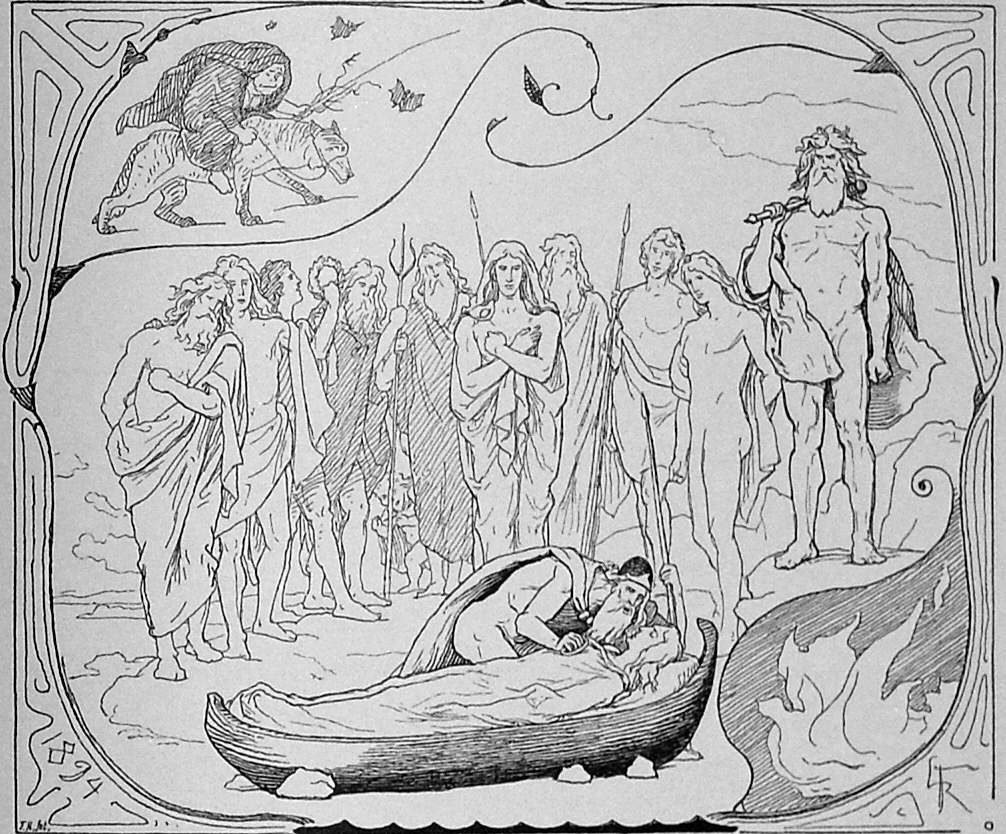

The Vikings believed that a kind of human vitality remained in a corpse after death, and this was integral in burial rituals.

Cremation helped this vital element detach from the body and pass into the realm of the dead and the divine.

Burning was a way of moving things between realms, which is why Odin’s Law said that a man could bring anything burned with him to Valhalla.

Odin placed his ring Draupnir on the funeral pyre of his son Balder to send it to him in Helheim.

Burned remains were then buried, which also transported items between realms.

Odin’s Law also states that a man can bring anything he personally buried in the ground (Ynglinga saga, 8).

The Viking community continued to deal with the life forces of the dead, in the form of honored ancestors for those who had properly crossed over.

But what about those who failed to make the transition ?

Returning as a Revenant

The Icelandic sagas make multiple references to people who did not rest comfortably in their graves.

It was believed that these revenants could return to terrorize the living, often haunting their own families and neighbors, especially at night, causing fear, illness, insanity, and death, and often leading to communities being abandoned.

One famous example of a revenant was Hrappr, in the Laxdaela saga (17), who haunted his old property to prevent others from occupying it.

Thorgunna, in the Eyrbyggia saga (51-55), could not rest until her dying wishes were properly honored.

The same saga records a kind of revenant epidemic, where man after man was killed and returned.

It says that in a community that started with a population of 37 (Icelandic communities were small), 18 were killed, five fled, and only seven remained (52-54).

Arguably fear of the dead increased during the transition from paganism to Christianity, when many of the Icelandic sagas were set, as at this time the Vikings stopped burning the dead and started direct burial to follow the Christian custom.

This meant that a key burial practice that helped prevent the dead from rising was not being carried out.

Some were believed to be more likely to return as revenants than others.

These included men with a particularly strong will or anger, anyone with unresolved conflicts, people with an unusual appearance, individuals skilled in witchcraft or other supernatural skills, such as berserker warriors, and larger women.

Preventing Posthumous Return

Many aspects of funerary rituals described in the Icelandic sagas were designed to ensure the dead stayed in the afterlife, where they belonged. Additional rituals were added when they feared that a certain person might return.

In these cases, those preparing the dead might approach them from behind or cover the head with something to prevent eye contact, as the eye of the dead was believed to be dangerous.

They might block the eyes, mouth, and nostrils to prevent the senses, and cut the fingernails.

They might be carried out through a hole made in the home rather than the door, to make it more difficult for the dead to find their way back.

When it was time to lay the body to rest, according to the Icelandic sagas, they took action to prevent rising.

They might lay stones on top of the dead to hinder their rising or create a large wall of stones around the burial mound to prevent passing.

People were sometimes buried in distant or remote places to make finding the way home challenging. If all this failed, they might decapitate the body with a sword and burn the body.

Decapitation is one of the methods most often mentioned in the surviving sources.

In Grettis saga (32, 35), the draugr Glamr is wreaking havoc after his death and Grettir stops him by cutting off his head and placing it against his bottom.

The sources also suggest that the head was seen as supernatural in some way and had the ability to live on after death.

For example, when the god Mimir was killed and beheaded by the Vanir gods, Odin was able to magically reanimate the head and install it at the Well of Wisdom to act as his eternal counselor.

Similarly, in Fljotsdoela saga (5), a troublesome giant is slain and his head cut off. Once his body has stopped contorting, his head was placed between his legs.

His remains were then cremated to prevent him from walking again.

Decapitation and burning were considered a last resort among the Christian Vikings who had to ascribe to the Christian belief in maintaining the integrity of the body for eventual physical resurrection by God.

Revenant Graves

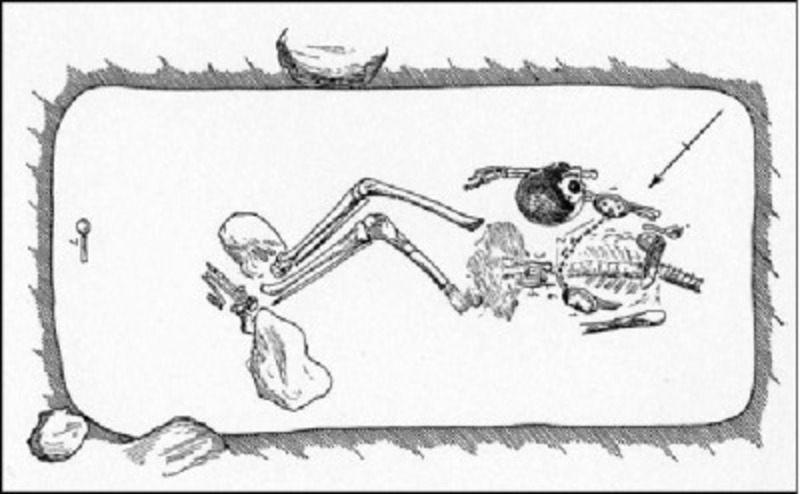

But are there examples of any revenant burials in the Norse archaeological record ? Possibly.

While there are certainly examples of decapitation and other measures that could have been meant to prevent the dead from rising, similar measures could have been taken for a variety of reasons, such as to punish a criminal or mark someone out as a slave.

So, while we can identify possible revenant burials, nothing is certain.

Take for example a cemetery at Slusegard in Denmark, which dates to shortly before the Viking Age, and contains ten decapitations, which seems a large number of mutilated corpses for a single cemetery.

Some may be revenant burials

Grave 309 contains the body of a male, probably aged 20-35, whose head has been removed but placed back above its shoulders.

His right arm and right foot were also both broken and inverted, which could have been a way to prevent the corpse from moving.

Grave 331 in the same cemetery contains the body of a person of unknown gender aged 20-35 who has been decapitated. The head was placed in a pot, and a large flat stone was placed above the pot.

Similarly, grave 438 contains the decapitated body, with the head placed in a bit beside the body with a piece of chalk and a flat stone covering the skull.

A 10th-century Danish cemetery at Bogovej in Langeland has a grave of a female, aged 30-40, who has been decapitated and their head placed between their legs.

The grave contains jewelry that seemed to have been displaced from its original position before being excavated.

This may suggest that the body was interred, exhumed and decapitated, disturbing the jewelry, and reburied.

That the purpose of these burials may have been to prevent rising is supported by a few runic inscriptions.

A bronze runic plate, called the Ulvsunda sheet and found in Uppland, Sweden, had an inscription on both sides, no bigger than a fingernail, is marked with 30 tiny runes.

It seems to be an incantation to prevent the dead person with whom it was buried from rising.

A reconstruction of the inscription may read “don’t be overly-lively out of the grave ghost, mat the evil-doer get woe.”

Similarly, the Nørre Nærå Kirke Runestone also seems to contain a spell to keep the dead in their grave.

Supernatural Beliefs

The pagan Vikings believed that they lived in a world populated by supernatural beings, and they believed in an afterlife, so it is not surprising that they believed the lines between the two could be blurred and that the dead could come back to haunt the living.

This is a common belief across many cultures as we all struggle with the question of what happens to us after we die and how to let go of lost loved ones.