Like everyone, the Vikings used numbers as part of everyday life and needed a way to write them down.

However, unlike modern English, which uses the Latin alphabet and Arabic numerals, the Vikings had their runic alphabet, but no separate designated numerals.

But that didn’t mean that the Vikings did not have a way to note numbers.

Furthermore, just as the Vikings believed that the runic alphabet was sacred and had magical properties, it is likely that numbers were also considered sacred.

Viking Numerals

Numbers are very rare in runic inscriptions, but they were almost certainly used in documents related to business transactions that have now been lost to time.

It is important to remember that unlike ancient Egypt, Scandinavia and other Viking territories did not have the environment for ephemeral documents to survive.

And unlike the Romans and later the Christians, the Vikings were not in the practice of writing extended prose and copying them for distribution and preservation.

The sagas were oral history until the advent of Christianity in the Viking world when Christian Vikings began using Latin to write down their stories.

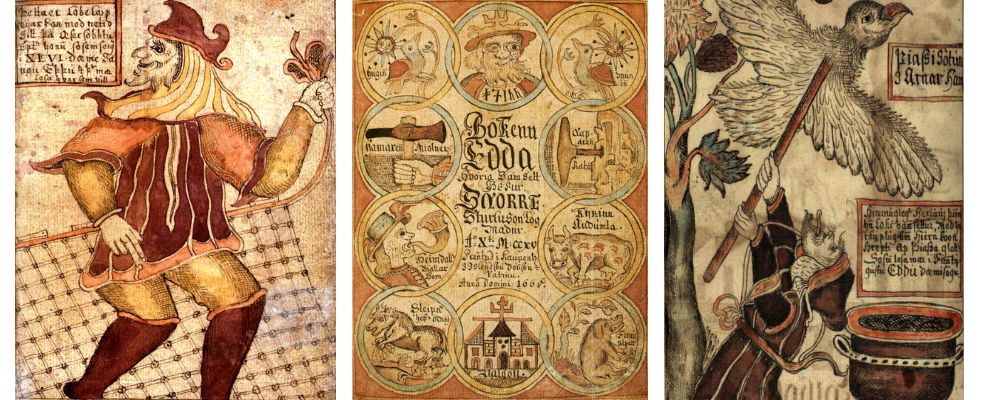

For example, the Icelandic Christian author Snorri Sturluson wrote his account of Norse mythology in a Latin text adapted to record the Icelandic language.

Numbers are rare in the surviving Viking inscriptions, but where they do appear, they appear in one of two ways.

First, the number could be written out in full like a word:

- ein = one/1

- tveir = two/2

- þrír = three/3

- fjórir = four/4

- fimm = five/5

- sex = six/6

- sjsu = seven/7

- átta = eight/8

- níu = nine/9

- tíu = tem/

- ellie = eleven/11

- tólf = twelve/12

- þrettán = thirteen/13

- fjórtán = fourteen/14

- fimtán = fifteen/15

- sextán = sixteen/16

- sjaután = seventeen/17

- átján = eighteen/18

- nítján = nineteen/19

- tuttugu = Twenty/20

- tuttugu ok ein = twenty and one/21

- tuttugu ok tveir = twenty-two/22

- þrír tigir = thirty/30

- tíu tigir = one hundred/100

- ellie tigit = one hundred and ten/110

- hundrað = one hundred and twenty/120

- hundrað ok átta tigir = two hundred/200

So, for example, an inscription might read ᛐᚢᛆᛁᛧᛐᛁᚴᛁᛧᚴᚢᚿᚢᚴᛆᛧ (tuaiʀtikiʀkunukaʀ), which reads “tveir tigir”, so “twenty kings”.

The Vikings also had specific words for ideas like first (fyrstr), second (annarr), third (þriðji), and so on, as well as double (tví), triple (þrennr) and so on. Sometimes, instead of writing the whole word, for commonly recognized numbers just the first letter would be given and interpreted from the context.

Although less common, the second-way numbers appeared was using the Greek system, where the letters of the alphabet are used to represent numbers.

In ancient Greek, “alpha” was used for one, “beta” for two, and so forth.

In the Viking Age, the Younger Futhark alphabet worked in the same way for numbers one to 16, since there were 16 runic letters in use.

This was particularly common for listing days of the week, using the numbers one through seven.

Calendars did not number the days of the month, but rather just listed the seven days of the week repeatedly.

Pentadic Numerals

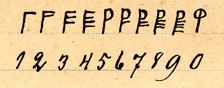

By the early modern period, the practice of using runic letters to represent numbers was replaced by what is known as the pentadic numeral system.

This is a notation similar to Roman numerals and was probably inspired by the Roman notation that would have been familiar.

A single vertical line forms the base of the numbers, and the number of horizontal branches going from left to right indicates the numbers 1-4.

At number 5 this was replaced with a D shape, and additional branches to represent 6-9.

For 0 and 10, an O is placed at the top of the horizontal line.

These numerals were then combined to make double-digit numbers, in the same way as Roman numerals.

But it is rare to see numbers higher than 19, as they only needed up to 19 for runic calendars.

Viking Magical Numbers

The Vikings believed that their runic alphabet was more than just an alphabet.

While each rune represented a phonetic sound, they also had symbolic meanings, like Egyptian hieroglyphics, and it was probably these meanings that were worked with when performing rune magic.

However, it is worth remembering that while we know that rune magic was used because there are often references to the practice in the saga, we do not know how it worked.

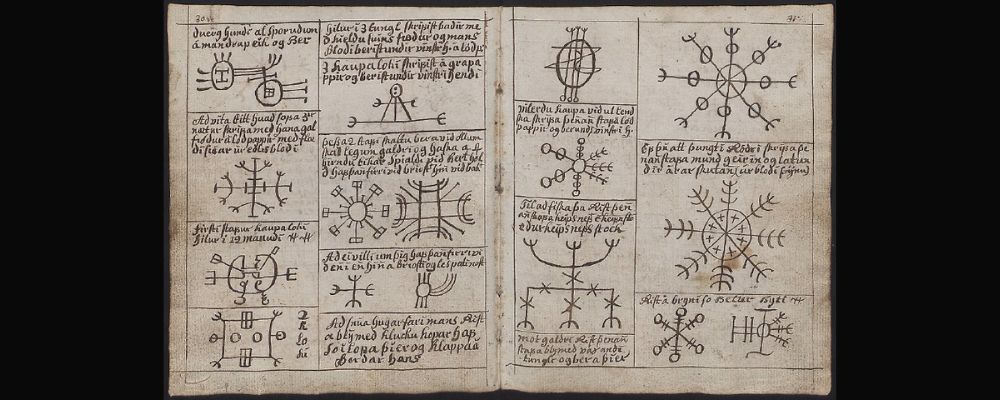

Icelandic magical grimoires from the modern era contain runic staves, which layer runes on top of each other to create magical symbols.

While it seems likely that runes were stacked to perform magic in the Viking Age, there is no evidence of any of the staves in the grimoires appearing in the Viking Age, and the texts of the grimoires show a heavy influence from Christian magical practices.

So, based on the fact that the Vikings believed their runes were magical, and used runes to represent numbers, it seems likely that the Vikings assigned some kind of sacred meaning to numbers.

We also know that many numbers were considered sacred or symbolic by the Vikings.

Number 9

The number nine was particularly important.

Odin hung himself from Yggdrasil for nine days and nights to learn the secrets of the runes. There were nine realms in the Norse cosmos.

The god Heimdall had nine mothers, Thor will take nine steps before he dies after slaying Jomungandr at Ragnarök, and so on.

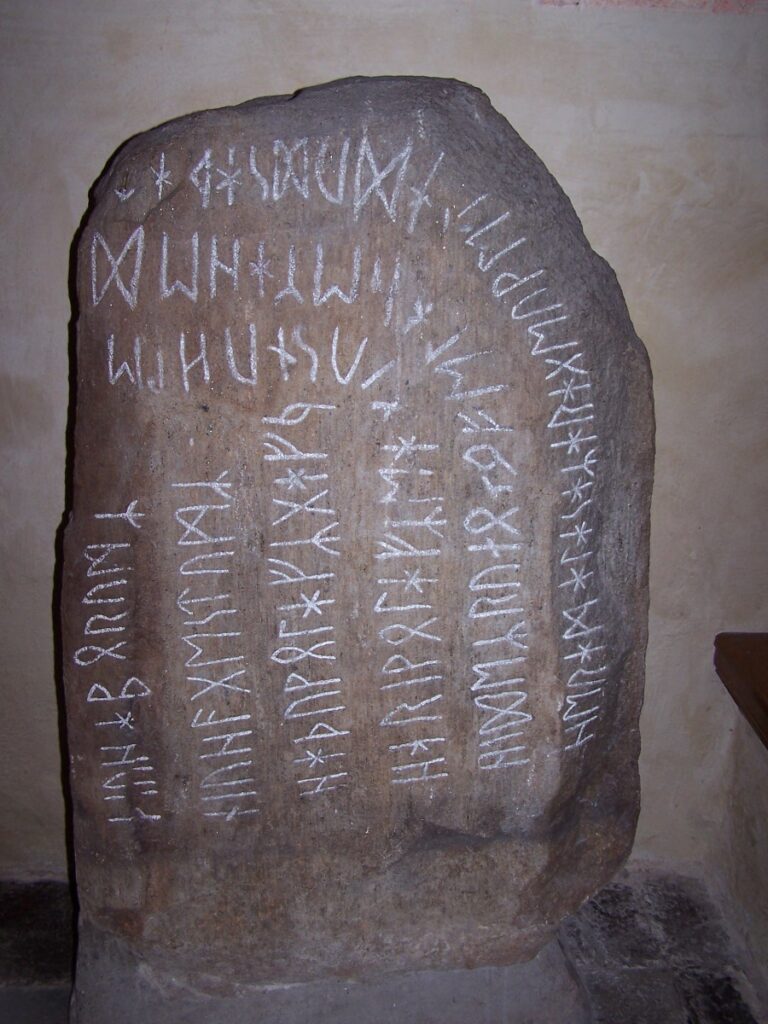

An early Norse runic inscription on the Stentoften Stone in Sweden records a festival in which nine goats and nine horses (all male) were sacrificed to bring fertility to the land.

The inscriber also declares himself a master of the runes and that he is invoking their power.

Number 3

The number three is common, with the gods often traveling in parties of three.

Odin, Hoenir, and Loki travel together to meet the dwarf king Hreidmarr, who had three sons, Regin, Fafnir, and Otr.

Odin forms a three with his two brothers Vili and Ve.

There are three Norns, Norse Fates.

There are three wells that feed the world tree Yggdrasil.

Number 4

The number four is also quite common. During creation, four rivers of milk flowed by the udders of the primordial cow Audumbla.

Four dwarves hold up the corners of the sky, and four deer live among the branches of Yggdrasil.

While it is a logical thought process that the Vikings probably imbued numbers with sacred meanings, any further insights into what those numbers may have meant and how they were used in modern speculation or invention.

The Uthark Theory

The most complex modern explanation of Viking numerology is known as the Uthark theory.

It started with the Swedish philologist Sigurd Argell working at Lund University in the 1930s.

While he was a serious academic, his theory has never been accepted by the academic community, but it is popular among Norse occult and esoteric groups.

The Uthark theory is based on several principles.

First, the Norse runic alphabet is called the Futhark alphabet, a name determined from the first six letters of the alphabet.

But Argell suggests that it should actually be the Uthark alphabet, starting with the Uruz rune.

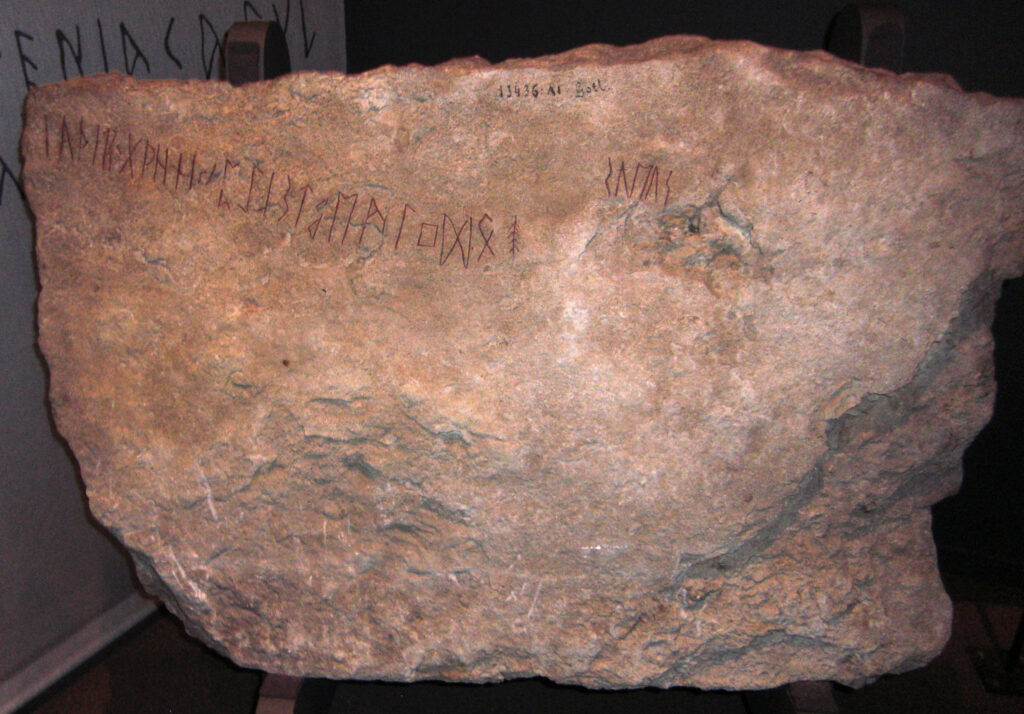

Some evidence for this might be found on the Kylver Stone, from Sweden and dating to around 400 CE. This stone was used to seal a grave and has an inscription on the underside.

The inscription gives the 24 runes of Elder Futhark, the version of the Futhark runic alphabet used before the Viking Age, in sequential order.

This find is part of the reason why the alphabet is called Futhark. But an alphabet inscription would seem strange for a gravestone.

It is suggested that the stone was not shaped or inscribed for that purpose, rather it was probably a stone used to teach the alphabet that was repurposed to seal the grave.

But Argell’s theory suggests that the stone was inscribed deliberately and that the inscription was meant to pacify the dead man in some way.

This is supported by the fact that the Fehu rune is either incomplete or missing and replaced by an I-rune, which Argell says is associated with death, making the inscription more appropriate for the burial context.

Justifying his reordering of the runes in this way, he claimed that each rune had a numerical value and esoteric significance that could only be understood with his new ordering, with the first rune, Uruz, representing strength and the beginning, and the last rune, which he suggests is the Fehu rune, representing wealth and the end.

Thus the runes track a spiritual journey from beginning to end in a similar way to the Major Arcana cards in the Tarot, which starts with The Fool and ends with The World.

You can learn more about the meaning of the runes within Uthark’s theory through a series of in-depth articles recently published in the Nordic Times.