If you are familiar with Greek mythology, you might notice many similarities with Norse mythology when you start reading about it (or vice versa).

This is not necessarily surprising. Many themes are recurrent in all human mythologies.

We find similarities between ancient Egyptian religion, the Mayan religion conceived millennia later on the other side of the world, and the Australian Aboriginal Dreamtime, despite Australia being cut off from the rest of the world for around 50,000 years.

These recurring themes speak to shared human experiences.

Similarities between Norse and Greek religions are even more likely since they both came from the same ancient Indo-European roots.

Plus, there was plenty of contact between the Greeks and Romans, who had very similar mythologies, and the ancient Germanic people, who would eventually populate Scandinavia and give birth to the Vikings.

While these similarities might not be surprising, they are still fun to explore.

Let’s look at some fun parallels between ancient Greek and Norse mythology.

Chaos Before Creation

According to Greek mythology, in the beginning, there was a great nothingness which is described as “chaos.”

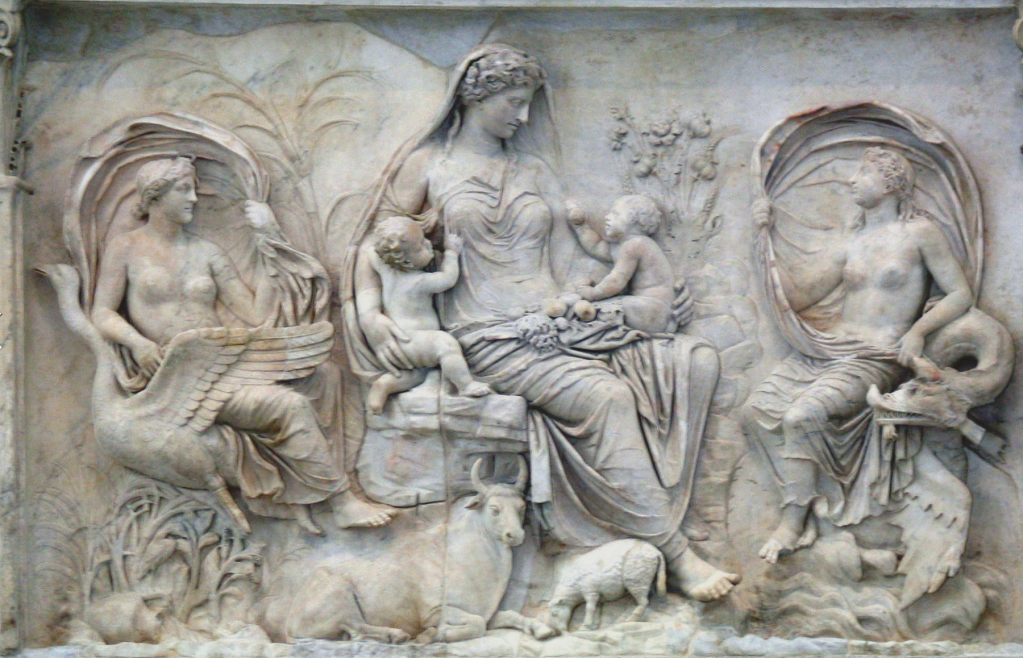

Gaia, the personification of Mother Earth and the ultimate mother of all things was the first thing to emerge from chaos.

Norse mythology also begins with a great nothingness, a void called the Ginnungagap.

But while the Vikings describe this as a great nothingness, they do not seem to have been able to conceive of something coming from nothing.

They incongruously also state that there were already two worlds in existence, Muspelheim, a world of heat and fire, and Niflheim, a world of cold and mist.

Elements of both these worlds seeped into the void and created a primordial goop from which life emerged.

The Earliest Beings

The first being to emerge from Chaos in Greek mythology is Gaia.

She was able to give birth by herself to Uranus, the sky god, and then they started having babies.

Their most important children were the proto-gods, the Titans, six males and six females.

But they also had other children, including the hideous one-eyed Cyclopses and “hundred-handed monsters.”

Uranus considered these creatures so abominable that he threw the Cyclopses and hundred-handed monsters into Tartarus, a black underworld dungeon, and also decided that no more Titans should be born.

Uranus’ decisions upset Gaia, so she convinced her Titan son Cronus to castrate his father and take his place as leader of the cosmos.

When he castrated Uranus, and from his gushing blood other beings were made including the Eumenides, chthonic goddesses of vengeance, the giants, a race of great strength, and the Meliae, ash tree nymphs.

The sea gushed forth from the testicles of Uranus and also gave birth to Aphrodite.

The first being to emerge in the Norse cosmos was Ymir, a primordial giant.

He fed on a primordial cow called Audumbla, who licked the first god, Buri, out of the primordial goop.

But it is Ymir who seems to be the equivalent of Gaia, going forth and giving birth to many monstrous beings.

His main children were the giants, who resemble the Titans in being similar to the gods but with a chaotic nature, but also strange beasts with 100 heads.

Buri gave birth to a much smaller number of beings, presumably because he had to do it the old-fashioned way by having kids with a giantess.

He was the father of Borr, who then had three sons of the giantess Bestla, Odin, Vili, and Ve.

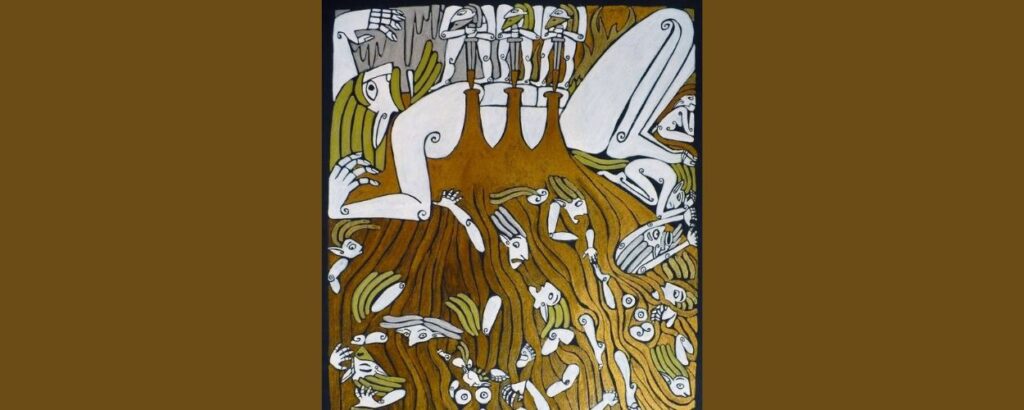

These three brothers were so concerned about the nature and number of beings springing forth from Ymir that they decided to kill the primordial giant.

When they did, they flooded existence with his blood, killing many of his offspring. Flood myths are common in most mythologies, including Greek, when Zeus floods existence to kill mankind and start over.

Odin, Vili, and Ve then used the body of Ymir to construct Midgard, the world of men and made the sea from the blood of Ymir.

Together they created mankind to populate Midgard, carving them from pieces of wood and the gods giving them different gifts.

This again matches Greek mythology, in which Prometheus created mankind from mud, and they were given life by the various gods giving them different gifts.

Wars of the Gods

Wars between the gods also feature in both mythologies.

Among the Greeks, the Titans first overthrew their father Uranus, only to be overthrown by their own children, the gods.

According to the story, Cronus married his sister-wife Rhea, and they started having kids.

But Gaia told Cronus that he would be overthrown by one of his sons, just as he had overthrown his own father.

To prevent this, Cronus started swallowing all his kids.

Rhea, wanting to save her youngest son, Zeus, fed Cronus a rock instead of the infant and sent him off to be raised in secret.

When he was grown, he came back and forced his father to regurgitate his siblings.

They then led a battle to overthrow the Titans and cast them all into Tartarus, becoming the new rulers of existence.

This was later followed by another war against the giants, which were among the other beings that emerged from the blood of Uranus.

Their battle seems to have happened during the age of man, because Zeus learned that only demigods could kill giants, and then had Hercules, his son by a human princess, summoned to help them win the battle.

The wars in Norse mythology are quite different.

The first war was the Aesir-Vanir War, between two races of gods, the Aesir led by Odin, and the Vanir gods who were more nature spirits and also practiced brother-sister marriages, which were considered taboo by the Aesir.

This is an interesting aspect, since not only was Cronus married to Rhea, but Zeus also married his sister Hera.

There is an account of the war with the Aesir using their military might and then the Vanir using their magic to get the upper hand.

The Vanir may have actually won the war, but they resolved on a truce rather than continuing the conflict.

The ongoing conflict that the gods have is with the Jotun, the giants in Norse mythology.

They seem to be sources of chaos, and the Aesir protect the cosmos against them.

However, at Ragnarök, the prophesied end of days, the giants will lead an army against the gods.

This will cause so much destruction that both sides will be destroyed, and the world will sink back into chaos.

Zeus and Odin

Both mythologies are polytheistic, with multiple deities, but each with a clear leader.

For the Greeks, it is Zeus, a sky god, and wielder of the thunderbolt.

Among his many attributes is an association with the eagle as a bird of augury.

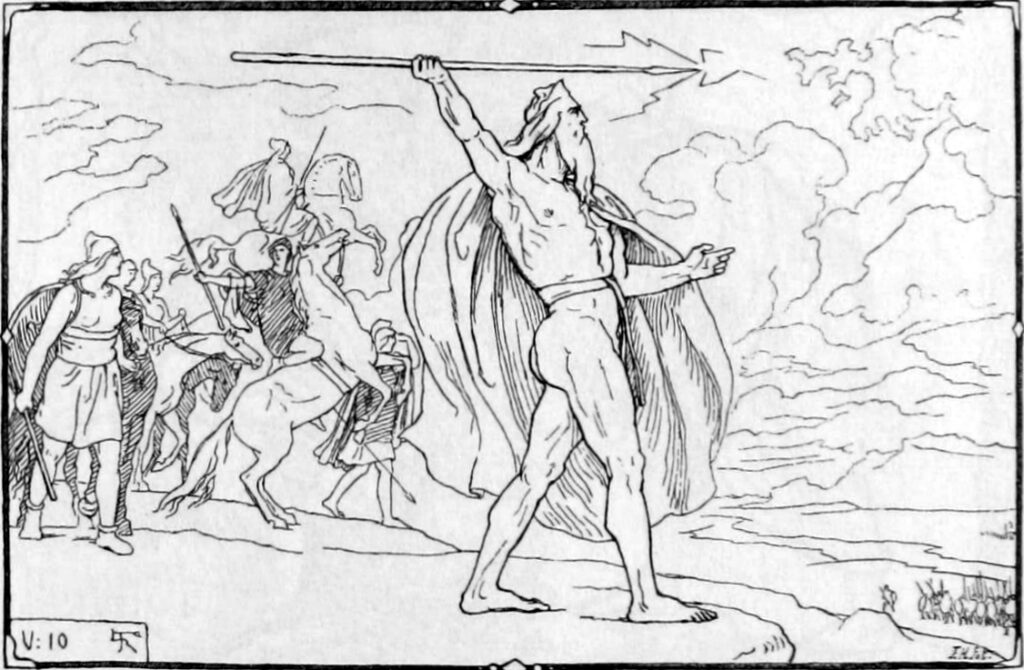

Among the Norse gods, Odin is the leader.

He is the god of war and wisdom, which makes him seem more like Athena than Zeus.

But he is also the All-Father and the progenitor of most of the Norse gods.

This is not dissimilar to Zeus, who is the father of most of the gods and heroes in Norse mythology.

Odin appears with a spear and his familiars are ravens, who act as the eyes and ears of the god in the world.

In some ways, Odin’s son Thor, the god of thunder, is more similar to Zeus.

But Thor does not wield a lightning bolt, he wields a hammer called Mjolnir, which creates lightning and thunder when he strikes.

It was made for him by the dwarves, the master craftsmen of the Norse cosmos.

Zeus’ lightning bolt was also made for him by the Cyclopses, who were considered craftsmen, or Hephaestus, the god of blacksmiths.

Most of the magical objects in Greek mythology stem from this source, just as most of the magical weapons we encounter in Norse mythology were made by the dwarves.

But in many ways, Thor is also similar to the hero Hercules, whose adventures to complete his 12 labors are some of the most important stories in Greek mythology.

Like Hercules, Thor is also described as the ideal warrior and the protector of mankind.

Many of the stories from Norse mythology relate to his adventures, usually as he travels to Jotunheim to deal with the giants.

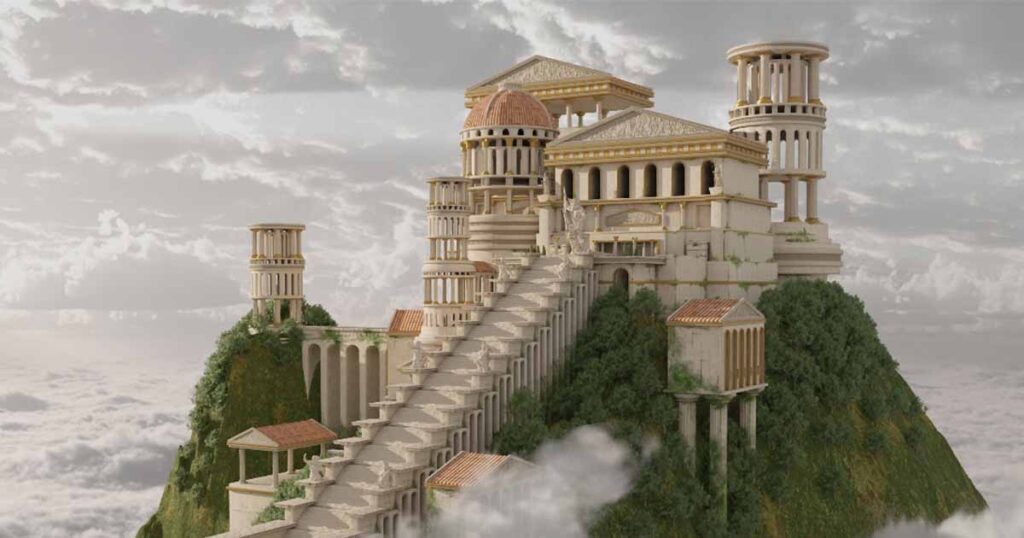

Mount Olympus and Asgard

The Greek gods dwell on Mount Olympus, which is described as a heavenly place from which they look down on the world of men.

Certain heroes, especially Hercules, can ascend to the heavens as a reward for their good deeds.

He is only one of many heroes to undergo this type of apotheosis in Greek myth, there is also Dionysus, Ganymede, Asclepius, Perseus, Andromeda, and many of the Roman emperors.

The Aesir gods live in Asgard, which is described as a separate heavenly world connected to the world of men via the Rainbow Bifrost Bridge.

It also offers a kind of apotheosis but is more narrowly defined.

When brave warriors die in battle, Odin may choose them to ascend to the heavens to live in Valhalla, his hall in Asgard.

There they feast and train, living alongside the gods, until they are called on to fight during the great final battle of Ragnarök.

The Underworld

Greek and Norse ideas of the underworld are also similar, defined as a place in the universe for all souls, not just the good or the evil, with the exception of those lucky enough to undergo some form of apotheosis.

In Greek mythology the underworld is often called Hades, though it has other names, for the Greek god Hades, a brother of Zeus, he oversees the underworld.

Among the Norse, it is Helheim, named for Hel, the giantess daughter of Loki who oversees the underworld.

Both are reached by a long and winding road through fields and over rivers and are supposed to be a place of no return.

Only certain heroes under certain circumstances can travel to the underworld and return unharmed.

Both underworlds also have guard dogs, Cerberus among the Greeks and Garm among the Norse.

Interestingly, the Norse god Hermodr is one of the few who has traveled to Helheim, sent to bargain with Hel for the life of Balder, one of the sons of Odin.

He is considered a messenger of the gods, just like the very similarly named Hermes in Greek myth.

Heroes such as Orpheus, Theseus, and Hercules also go to Hades to try and retrieve lost friends.

Like Balder, who finds himself stuck in Helheim, where Hel treats him as a prince, Hades kidnaps Persephone and takes her to Hades.

She is unable to return because she has eaten the food of the dead, which is why she is destined to spend half the year in Hades and half the year above, accounting for the seasons.

Persephone is an agricultural goddess, while Balder is a god of light.

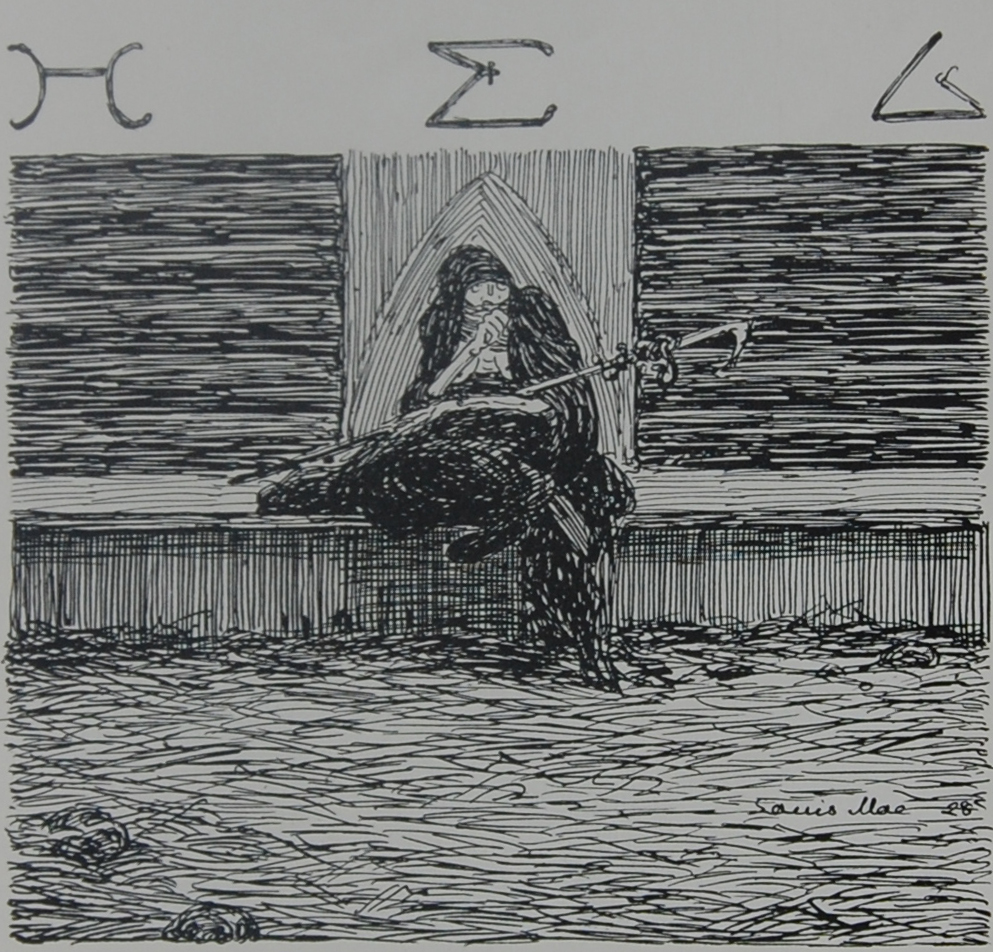

Fate and Destiny

Both mythologies also place a strong emphasis on fate and destiny, and the idea that one’s path is laid out for them.

Prophecies are commonly delivered in both mythologies, often by Oracles among the Greeks and by Volva seeresses among the Norse.

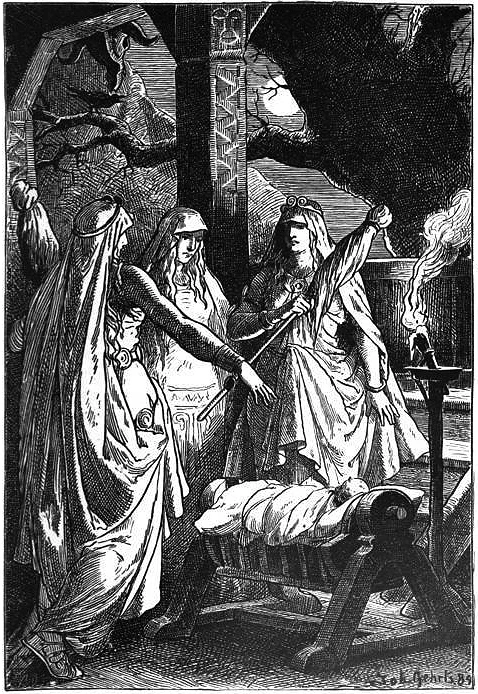

In both Greek and Norse mythology, there are also goddesses of fate, which seem to exist in an unknown number as personal deities, but there are also three principal fates.

Among the Greeks, these are the Morai, Clotho (the spinner), Lachesis (the allotter), and Atropos (inevitable death).

Every person’s fate is represented by a spun thread, and the fates are responsible for ensuring that everyone fulfills their destiny.

Even the gods must obey their rules of destiny.

In Norse mythology the Norns function in a similar way.

There are many Norns, but there are three principal Norns that live at the Well of Destiny.

They are often described as weaving fate on a loom, and they arrive at the birth of each person to measure their portion of life.

They are three sisters, the eldest is called Urd, which means what once was, the middle sister is Verdandi, which means coming into being, and the third sister is Skuld, which means that which shall be.

Again, not even the gods can escape death, as evidenced by their inevitable deaths at Ragnarök.