Asatru is a modern neo-pagan reconstruction of Old Norse pre-Christian beliefs, with a religious structure of its own, and surprisingly on the rise in many countries these past fifty years, especially on European countries and in North America.

Please consider taking a look at the video on Asatru produced by Arith Härger:

What is the religion Asatru? And what does the word “Asatru” mean?

Asatru the name created by the followers of the Nordic neo-pagan religion during the 19th century, to designate the modern reconstruction of the religious traditions of Scandinavia before the introduction of Christianity.

The name roughly translated means “to be true to the Æsir”, one of the tribes of Norse gods depicted in Norse mythology.

Although I must reinforce that this is the common designation and that the origins of the name might come from the old Norse word ǫ́ss or áss (plural æsir), meaning the “principal” pantheon in Norse religion; and from trú, meaning “faith” – “The faith of the Æsir”.

Therefore, during the 19th century, Asatru meant to be true to the Norse gods in general, to be faithful and worship the Norse gods and their symboles, but with the increasing knowledge about pre-Christian Scandinavian pagan traditions, and with the creation of other branches of this pagan faith, Asatru also became the term to refer to a religion much more focused on the Æsir tribe of gods.

Since when does Asatru exist?

The 19thcentury was the period in which archaeology started to progressively awake some interest within the European nobility. It became an amateur activity for the wealthier members of the society , because it was very prestigious to have such an occupation as a hobby.

Consequently, the interest in archaeology grew and 19thcentury nations whose political notions turned around nationalism and the need to find a common past to unite the masses and new nations under construction, turned to archaeology for answers.

People became aware of their past, and because the 19th century was a historical period of great changes with the increasing process of industrialization and the abandonment of traditions and the family in

Returning to the roots didn’t mean people wanted to return to a religious pagan past, rather, they wanted to return to the land, to tradition, to the domestic and farming activities less stressful and depressive when compared to the new reality of

The archaeological and historical perception of ancient European civilizations was that the ancestors of modern Europeans worshipped nature, and this was the line of thought that perfectly fit into both the associations devoted consciousness of the 19th century, and the political ideas of nationalism – to return to the land, to be auto-sufficient, family values and traditions.

In this way, many pre-Christian European cultures were seen as nature-worshippers. Which wasn’t far from the truth to a certain extent, since the archaeological interpretations of the time were focused on European civilizations from the Neolithic onwards; civilizations whose societies turned around the seasons – planting the soils, harvests, storing food for winter, and so on.

This led to the belief that pagan European societies were nature worshippers and most of their gods and goddesses were fertility deities.

However, during the 20th century, to be more precise during the early 1970s, groups of people from Iceland, the United States and the British Isles, more or less at the same time, formed new religious association devoted to the revival of the ancient religious beliefs and practices of pre-Christian Northern Europe, particularly those of pre-Christian Iceland and Scandinavia but also the related traditions of the Germanic peoples of continental Europe and the Anglo-Saxons of England. Ásatrú gained a new meaning and progressively became a faith with strong

Asatru isn’t an ancient religion, older than Christianity. Asatru is a modern neo-pagan religious reconstruction, focused on the set of religions and spiritualties which springs from the specific spiritual beliefs of pre-Christian Northern Europe.

Obviously, our Norse ancestors did not refer to their religions as Asatru. In fact, pre-Christian Scandinavians did not subscribe to one single religion, but to many cults belonging to a spirituality with similarities shared by various pre-Christian tribal communities scattered all over Northern Europe.

These ancient faiths were revived as Ásatrú in the 19th century as previously said, although it received a special boost in the late 1960s and early 1970s when Sveinbjorn Beinteinsson (poet and a farmer) was the instrumental figure in getting Ásatrú recognized by the Icelandic government in 1973 and from that moment on several organizations started to appear all over Europe and in North America.

Is Asatru a recognized religion?

Sveinbjorn Beinteinsson with a group of friends, many of them also poets and devotees of early Icelandic literature, formed the association known as Asatruarfelagid, “the fellowship of those who trust in the ancient gods,” quite often described as Ásatrú.

In the United States, Stephen McNallen and Robert Stine formed the Viking Brotherhood, which was soon renamed the Asatru Folk Alliance, and in Great Britain, John Yeowell and associates formed the Committee for the Restoration of the Odinic Rite.

These were the first recognized Neo-Pagan revival organizations of the

It’s clear that a wide variety of people are embracing Northern European pagan traditions, and most of them speak of their faith as Asatru or calling themselves Ásatruar (“Ásatrú believers”).

Alternately, they also refer to themselves as Heathens (the ancient Germanic term for non-Christians)and their religion as Heathenry. Those less aware of what Ásatrú is, often refer to it as the “Religion of the Vikings”, and in general during the faith is seen as “Nature Worship”. So first things first.

Let’s start clearer religious why Ásatrú is referred to as “The Religion of the Vikings”:

As previously said, during the 19thcentury and early 20th century, archaeology was greatly led by nationalist minds. They were trying to find a common past in each other’countries to have a reference and a factor that showed such nations were once united under one single culture. To Central Europe it was the Germanic; to Great Britain is was the Anglo-Saxons and to the Scandinavians it was the Vikings (although being a Viking was a profession and a way of life, and not a specific ethnical group, but it was a culture nonetheless).

The Viking Period was practically what placed Scandinavians in the books of history. Not much was known about center before the Viking Period, which was precisely a time when Scandinavians introduced themselves to the rest of Europe.

Viking Age archaeology was the means of finding a common culture that in the past united Scandinavians, and this historical fact was the key point of nationalist politics of Scandinavia, especially of Norway, during the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century. Subsequently, the Viking culture became widespread and very much a trend with J.R.R.

So a religion such as Asatru was easily referred to as “The Religion of the Vikings”, due to its obvious connection with the Norse myths and folklore, but also because the formation of Ásatrú and its basic religious beliefs are very much

Asatru has Been Described as a “Nature Religion”. What Does That Mean?

In terms of being a religion referred to as“Nature Worship”, much of this stigma comes from the

Within Asatru itself, at least the original founders and the very first generations of followers, there is a strong belief that the Gods manifest themselves through nature, and this reinforces the belief that Ásatrú is a Nature-Worshipping Religion.

However, with the increasing modern heathens in various academic fields of social-sciences, we came to progressively reshape the idea around Asatru as a Nature-Worshipping faith. Pre-Christian Norse and Germanic peoples seldom had faiths around nature-worshiping.

It’s more common to see in the archaeological record cults around death, the ancestors, war and magic, then fertility cults or cults based on a spiritual notion that we can immediately connect to nature.

Certainly there were fertility cults and other cults around nature; a person could worship Freyja in her fertility aspect, to care for the crops and cattle; groups of people would worship Freyr in cults related to this deity as a fertility god; others would worship Njördr for plenty, a good catch on high seas; some would worship Ullr for good luck in hunt, etc.

But the gods had many aspects, and the same people who sometimes worshiped Freyja and Freyr, or any other deity in

In fact, until quite recently, even within Asatru (especially within Ásatrú), it was believed that magic had a secondary role in pre-Christian Scandinavian beliefs.

This is something I (as an archaeologist and historian), and others in the academic field of

This is a change on the perspective people had of Ásatrú. Maybe, Ásatrú wants to continue to be

We Keep Talking About the Vikings. Does This Mean That Asatru is Only for People of Scandinavian Ancestry?

Perhaps one of the most important questions that arise when people want to know more about Asatru, is if Ásatrú is Only for people of Scandinavian ancestry?

It’s true that Ásatrú has been

And there is even that stigma of Neo-Nazism and far-right political parties involved with Ásatrú. Many studies have been conducted due to the tendency of linking Norse Paganism to certain racist and Neo-Nazi elements within the Nordic Pagan communities.

Unlike what is led to believe that Ásatrú is filled with Neo-Nazis, the great majority of modern Nordic Pagans devoted to Northern European cultural heritage, are firmly opposed to Nazism and racism. The minority of NordicPagans with Neo-Nazi and far-right political perceptions are firmly denounced by most modern Nordic Pagans, as being members of groups most Heathens wish to have nothing to do with. Within Heathenry, there is a constant fight against racism and Neo-Nazism.

In reality, the number of non-Europeans who practice Northern European pagan traditions has increased since the early

Asatru in America began to encourage people to seek their cultural-heritage, but let’s not have a miss-interpretation around that. This doesn’t mean that the pride in ethnic heritage felt by Nordic Pagans is linked to racism, nor should devotion to Nordic culture be wrongly equated with Nazism.

It began by simply seeking cultural-heritage and embrace it. Nowadays, at least in Europe, Ásatrú and other forms of Heathenry isn’t much to seek cultural-heritage but to seek a spirituality that fits into our cultural perceptions.

This increasing shift from organized religion into spirituality gave freedom for other people to embrace the Norse gods and Old Nordic traditions. There are many people, even organizations, from Non-European and Non-Northern American backgrounds who embraced this faith.

Is the Norse religion still practiced?

Nowadays Asatru religion has hundreds of followers all over the world, especially organizations in the United States and Europe; in

What are the Basic Beliefs of Asatru?

In

They are mainly guiding lines in how we should conduct our lives in order to achieve greatness and enjoy this world, taking the best advantage of everything that surrounds us, and as such, the gods are often seen as part of nature and often manifest themselves through nature, and we

lthough it’s necessary to point out that we are on our own and we only communicate with the gods for help when all human efforts and recourses have been spent, and there is no other option, because when worshipping the Norse gods, a gift calls for a gift, and so sacrifices must be made, often in the form of ceremonies when the community shares with the gods personal objects, food, drink, etc., to maintain strong the bounds of friendship between us and the gods.

What are the Standards of Behaviour Taught in Asatru?

Asatru adheres to the Scandinavian pagan believe that objects play an important role in the religious connection with the gods, the gods can infuse objects with power, there is a flow of energy which lies within all things.

For instance, we create something, we bend our thought to it, we give it shape and so we give apart of ourselves to the object, it is infused with our essence.

This can be given to the gods as an offering and in

We require this force, the

How is Asatru religion Organized?

The Ásatrú organizations are known as Kindred.

The priests of a Kindred are known as Gothar, the plural form of

This is an important aspect of this religion, because

The ceremonies performed within the kindred are known as blóts(Old Norse “Sacrifices”; blóta – to worship, hallow or sacrifice), and the altars on which the

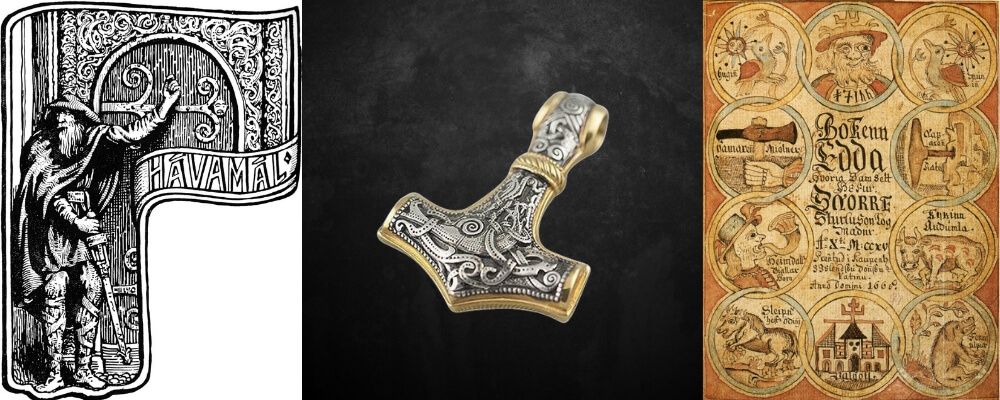

The Asatru bible, does Asatru Have a Holy Book, Like the Bible?

There is no Asatru Bible but for people to become Gothar, the “priests

- The wisdom of Odin,

- The strength of Thor

- The love of Freyja.

These 3 aspects are often expressed by possessing sacred texts, be part of a Kindred and care for the Folk. Guiding the Kindred with wisdom, being strong for the community and work for the benefit of the community, which also requires a certain amount of love, friendship

The Gothar also need certain items to perform the rituals, like the hammer of Thor

The Hávamál is not seen as a definite holy text. The Hávamál is a poem that establishes the guidelines of Ásatrú. There are other sources of knowledge, of course, often used but the Hávamál is a very important poem in the modern religious structure of Ásatrú, and mind that I continue to reinforce that I’m speaking about Ásatrú the modern reconstruction, and not the pre-Christian Scandinavian religions.

In

Like many modern pagan reconstructions, this is a religion that shapes itself to our modern needs, and as such, many Ásatrúorganizations may do things differently, but the cannons of this religion, the basics, are the ones I’ve just mentioned. Of

Ásatrú is the most famous Nordic neo-pagan branch and although there are clear differences from organization to organization, the foundations of this religion still cling to the 19th century religious reconstruction, and indeed the gods people worship in this religion are mainly the Æsir, such as Odin, Thor, Týr, Baldr and also two Vanir deities often included – Freyr and Freyja.

The other gods are seldom heard

What are the Runes, and what do They Have to do With Asatru?

The Runes played an important role in Pre-Christian Scandinavia. They were not just a form of writing but also used in all sorts of religious and magical activities.

Nowadays, within Ásatrú, runes have the tendency to be used as a writing system, whilst in other branches of Northern European pagan

Rune poems are the original literary sources from which the knowledge of the meaning of each rune comes from, and such interpretations are currently in use more or less the same way the Hávamál is used in Ásatrú – as guiding lines.

Does Asatru Involve Ancestor Worship?

When it comes to worshipping the Ancestors, it’s a question that can hardly be answered in a short text. But suffice to say the pre-Christian Scandinavian peoples worshipped their ancestors.

We have references of festivities such as the Dísablót, Álfablót, “Cult of the HearthFire”, and private celebrations in burial mounds, hills

What is performed nowadays in religious terms connected to the Ancestors, are modern recreations (shared either with the community or in private) based on the little information

For now what can be done is to compare the archaeological findings and the historical references of pre-Christian Scandinavia, with contemporary living communities whose spiritualties are very much based on polytheism, shamanism

How Does Asatru Differ From Other Religions?

So this is what Ásatrú is, a neo-pagan polytheistic reconstruction based on certain religious and historical aspects of pre-Christian Scandinavia. and Scandinavia of the pre-Christian indigenous faith of the Norse peoples.

Nevertheless, it’s important to refer that the believers of this faith attempt to interact with the Norse gods and in addition they recognize that other people have their own gods, so by no means do the followers of Ásatrú believe that their gods are the only true gods.

It is a religion, or a reconstruction of a religious tradition, without a hierarchical structure, dogmas, or sacred books being the center of the entire religion, and as such, the religious practices may suffer a lot of changes and different interpretations according to the social environment in which they are inserted.

References:

Amster, Matthew H.; (2015). “It’s Not Easy Being Apolitical: Reconstructionism and Eclecticism in Danish Asatro”, in Rountree, Kathryn, Contemporary Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Europe: Colonialist and Nationalist Impulses, New York and Oxford: Berghahn, p. 43–63.

Asbjørn Jøn, A.; (1999). “‘Skeggøld, Skálmöld; Vindöld, Vergöld’: Alexander Rud Mills and the Ásatrú Faith in the New Age”, in Australian Religion Studies Review, 12 (1), p. 77–83.

Blain, Jenny; Wallis, Robert J.; (2009). “Heathenry”, in Lewis, James R.; Pizza, Murphy, Handbook of Contemporary Paganisms, Leiden: Brill, p. 413–432.

Boyer, Régies; (1986). Le monde du double: la magie chez les anciens Scandinaves. Paris, Berq International.

Calico, Jefferson F.; (2018). Being Viking: Heathenism in Contemporary America, Sheffield: Equinox.

Cragle, Joshua Marcus; (2017). “Contemporary Germanic/Norse Paganism and Recent Survey Data”, in The Pomegranate: The International Journal of Pagan Studies, 19 (1), p. 77–116.

Gregorius, Fredrik; (2015). “Modern Heathenism in Sweden: A Case Study in the Creation of a Traditional Religion”, in Rountree, Kathryn, Contemporary Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Europe: Colonialist and Nationalist Impulses, New York and Oxford: Berghahn, p. 64–85.

Harvey, Graham; (1995). “Heathenism: A North European Pagan Tradition”, in Harvey, Graham; Hardman, Charlotte, Paganism Today, London: Thorsons, p. 49–64.

Haywwod, John; (2000). Attitudes to sex, in Encyclopaedia of the Viking Age, London, Thames and Hudson, p. 169.

Horrell, Thad N.; (2012). “Heathenry as a Postcolonial Movement”, in The Journal of Religion, Identity, and Politics, 1 (1), p. 1–14.

Jónína K. Berg; (2004). “Sveinbjörn Beinteinsson skáld og allsherjargoði frá Draghálsi” from Vor Siður, No 5, p. 5-6.

Kaplan, Jeffrey; (1996). “The Reconstruction of the Ásatrú and Odinist Traditions”, in Lewis, James R., Magical Religion and Modern Witchcraft, New York: State University of New York, p. 193–236.

Langer, Johnni; (2005). Religião e magia entre os vikings: uma sistematização historiográfica, in Brathair 5 (2), p. 55-82.

Paxson, Diana L.; (2006). Essentinal Ásatrú, walking the path of Norse Paganism, Citadel Press, New York.

Paxson, Diana; (2002). “Asatru in the United States”, in Rabinovitch, S.; Lewis, J., The Encyclopedia of Modern Witchcraft and Neo-Paganism, New York: Citadel Press, p. 17–18.

Price, Neil; (2005). L’sprit Viking: magie et mentalité dans la scieté scandinave ancienne, in Boyer, Régis, Les Vikings, premiers européens. Paris, Éditions Autrement, p. 196-216.